The Evolution of the Poodle

by Wendell Sammett

From the archives of The Canine Chronicle

Let us pay tribute to our foreign and American breeders of the past. The men whose painstaking work for generations helped to create our breeds of today.

Selective breeding began thousands of years ago when our ancestors were gradually adapting a pastoral life.

Prehistoric people had already succeeded in domesticating dogs, which lived near their dwellings as hunting companions for thousands of years. Over the millennia, our ancestors eventually came to perfect certain types of dogs for a purpose, such as hunting & working & companions.

Let us make no mistake, selection alone, whether natural or created by humans, could never have transformed different breeds, without the patience of the breeder waiting for this breed to happen.

It was not until the 18th century, however, that the concept of genealogy began to develop and to become precisely defined.

Although not in general use, the notion of keeping track of breeding stock had been exploited by the Arabs for centuries. They were the first to inscribe the names and descriptions of their stallions and mares on tablets. By recording the ancestry of their favorite mounts and fastest runners, Arab breeders were able to crossbreed the descendants of these horses to produce progeny that possessed the same traits.

But it was in 18th century England that breeders actually implemented the system that would become an important step forward in the improvement of animal breeds. By the 18th century, English breeders had established stud books so that breeders could create animals of consistently high quality with full knowledge of their ancestry.

However, genealogy alone, important as it is, could not have promoted the formable reproduction of animal species within the space of a century, as is evidenced in the breeds we have today. If we compare the dogs of today to those of the early 1900’s, the difference between the dogs and their descendants is striking. Although the earlier dogs seemed well-built, they fall far short of the shape, size, weight, performance, traits, and surely even in disposition of its breed today.

Such unprecedented progress would be inexplicable were it not for the essential role played by the laws of heredity and their application and development in all breeding practices.

The laws of heredity were eventually accepted and developed in the early 1900’s. It was at that time that genetics began to attain the important place in animal husbandry that it has occupied ever since. This specialized branch of service helped breeders to understand, and in some cases control, the role of dominant and recessive genes, with its advantages and disadvantages. Genetics also made it possible for breeders to carry out inbreeding and line-breeding, thus contributing to the developing of new breeds.

At the same time, technical progress was made in agriculture, producing different types of grains leading to better food for animal health, and a dramatic progress was made in veterinary science. As a result, breeds developed in the direction of healthier dogs. By the mid-century it seems that perfection was at hand, but the art of breeding had yet to be revolutionized by a technique, artificial insemination, developed after World War II. And now we have frozen semen and cloning.

Legend has it that artificial insemination was developed in the 14th century, when the Arabs were intent on improving their horses. In 1780, the Italian biologist, Lazzaro Spallazani demonstrated the possibility of using artificial insemination in dogs, but the technique was not taken seriously or perfected until many decades later, notably by the Russian biologist, Ilya Ivanov, about 1907. The technique of freezing semen for storage was perfected in the 1940’s and improvement continues to be made.

This brings us to the chasm that separated serious breeders from biologists who specialized in artificial reproduction.

At the risk of disappointing genetic engineers, cloning specialists, and other sorcerer’s apprentices, I am sure that the future of breeding is definitely not in their hands. Whatever talent and expertise they may have, these scientists will never merit the noble title of breeders. At best they may become manufacturers of living copies, but the progeny that survive from their test tubes, however successful they may have been – can never compare to the actual breeders unlimited patience, intelligence and loving passion that inspires every breeder worthy of their title as a Good Breeder. It is the good breeder who refrains from eliminating an animal from his breeding stock that has a good gait, temperament and type. He strives to preserve good lineage that can subsequently be improved from one generation to the next by experimental breeding not simple trial and error.

That is what dog breeding is about, aiming for perfection without ever forgetting that no matter how splendid the animal produces, its genes can always be used to obtain a more desired specimen. This is the manner in which breeders over the centuries have improved our dogs. All have become healthier and more beautiful.

All of the early authorities agreed that Poodles were represented in three countries, Germany, France and Russia. And later came the three sizes, small (not toy), medium and large.

Each country’s Poodle was represented with differences in type, coat, and thickness or bone.

The Poodle was called various names in relation to its country. In France, he was known as the Grand Barbet, the small size was Petit Barbet, and others were Caniche, Mouton and Moufflon. While in Germany he was named Pudel, meaning “to splash in water.”

The “Mouton Poodles of France” were used for draught dogs as well as retrievers, truffle hunters and circus actors. These earlier dogs were sturdy, thick-set, with wide skulls, light round eyes, rather short necks, fairly high set ears, and thick wooly coats. In comparison to the other French Poodle, the “Caniche” or the German “Pudel” were slighter in build.

(Note, the underlined appears in our Poodle Standard today.) Mr. Furness in his monograph on the Caniche and Pudel, published in 1891, describes them as follows: “The skull should show a well-defined stop. Very broad across the ears and a pronounced dome. The neck should be rather long, the shoulders upright, the barrel well-ribbed up, with a strong arched loin. The feet should be strong and muscular, the hind legs are straighter than those of the German Pudel, giving the dog a proud but stilted action when walking. The coat tightly curled and somewhat wooly in texture.

Mr. Furness preferred German Pudel. He states, “it is the type of the family that is powerful, compactly built, with a deep narrow chest, a strong loin slightly arched, with a square back, powerful hindquarters to propel him through the water; round compact feet with toes webbed to the nails. The head is wedge-shaped, very broad, and flat between the ears,” and he adds that the coat will cord in long strands.

The Russian Poodle was not like a Greyhound in type, with a wiry, springy coat, and was higher on leg, a much slighter-boned dog, though larger in size than either the French or German.

Vero Shaw much prefers the Russian Poodle saying that “the Russian Poodle proper should be lithe and agile, while in central Germany, the black Poodle seems to be thicker in legs, and have slight muzzles, assuming more staid, sturdy and aldermanic proportions.” He describes the prize-winning Russian dog as being 20-1/2” high and weighing 31 lbs.

Earlier writers considered the woolly-coated Poodles as separate from the corded. Herr von Schmeideberg, an early canine authority, called the wool-coated dogs the Schaaf Pudel (Mouton) and the pedigreed Poodle was corded in coat, Der Schaaf Pudel, while many persons credit Russia with the origin of the corded Poodle.

Mr. Crouch, of the famous English Poodle Kennel, did not believe that the corded Poodle was a separate variety. Mr. Crouch stated that any Poodle’s hair can be corded if handled with care. We know that neglected Poodles develop mats, or felt, and they show a cording tendency.

The “Lion Trim of the Poodle” was noted on Roman tombs and Greek and Roman coins. It is hard to imagine that these were Poodles, but actually could be any full coated dog, clipped into a modified “Lion Trim.”

Poodles, as retrievers, were known for their thinking ability, having a keen nose with a strong sense of smell, and being a tireless swimmer. The Poodle’s tremendous heavy coat was a drawback. This started the custom of the “Lion Clip,” by shaving the hindquarters from the ribs to the stern, giving freedom for easier power, and leaving an abundance of hair covering the dogs’ front and rib cage, protecting his organs, such as heart and lungs, from freezing water. Hair was also left on the joints for protection. The “English Saddle” was also recognized as a trim with short hair covering the joint or the hindquarters.

No doubt, remnants of characteristics and conformation of the early German, French, Russian and English Poodles are found in our Poodles today, with the variations of conformation, proportion, and refinement.

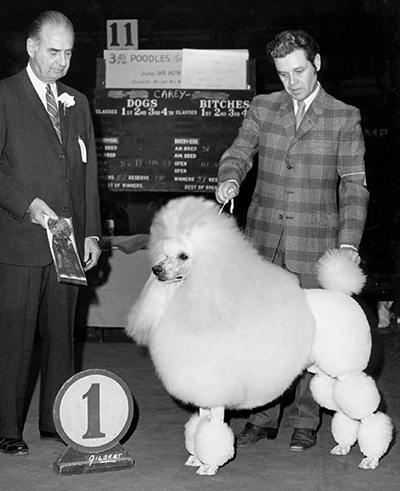

With the methods of breeding and the written Poodle Standard, the Poodle has been refined in type and appearance as an elegant, squarely-built, well-proportioned dog, who carries himself proudly. Properly clipped, the Poodle has an air of distinction and dignity peculiar to himself.

This, no doubt, comes from the rich heritage that is behind the modern-day Poodle.

Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=195356

Comments are closed