The Story of the West Highland White Terrier

Click here to read the complete article

290 – August 2019

By Lee Connor

But these distinctive dogs aren’t (relatively) modern day creations. There is considerable evidence to suggest that small ‘rough-haired’ white

But these distinctive dogs aren’t (relatively) modern day creations. There is considerable evidence to suggest that small ‘rough-haired’ white

terriers have been very much a part of life in the Western Highlands of Scotland for a considerable time.

This is a wild, rugged and unforgiving place.

Colonel E.D. Malcolm of Poltalloch, the name most closely associated with championing the breed in its early days, wrote most eloquently of his homeland, and I always feel that to truly understand any breed you must have some knowledge of the land and the people that have shaped and created it.

He wrote; ‘Anyone who looks at a map of Scotland must be struck with the way in which ice and sea have worked together to plough long valleys out of the hills and fill them up with salt water. Sometimes even more than that has been done – the water has got all round the land and separated it from the main mass, cutting most marvellously into what has been taken, as a glance at the Island of Skye – the Winged Island – or at the Outer Hebrides will show.

In this way the Western Highlands of Scotland are endowed with a sea coast of marvellous length. It is said for instance, that there is no spot in the county of Argyll more than five miles, as the crow flies, from the sea… the sea has for the most part taken away the soft stuff and left only hard rocks.’

And it was here, amongst the impenetrable rocks and boulders, that the badger, fox, otter and the almost-extinct Scottish wild cat found a safe haven.

Impenetrable and safe that was until man made use of his terriers to bolt these vermin.

Malcolm wrote in 1907 about the difficulties faced by these dogs:

‘The West Highland Terrier of the old sort – I do not, of course, speak of bench dogs – earn their living following fox, badger, or otter wherever these went underground, between, over or under rocks that no man could get at to move, and some of such size that a hundred men could not move them. (and oh! The beauty of their note when they came across the right scent!)

I want my readers to understand this, and not to think of a Highland fox cairn as if it were an English fox-earth dug in sand; nor of badger work as if it were a question of locating the badger and then digging him out. No, the Highland badger makes his home amongst the rocks, the smallest ones perhaps two or three tons in weight.

No digging him out and, moreover, the passages between the rocks must be taken as they are; no scratching them a little wider. So, if your dog’s ribs are a trifle too big he may crush one or two through the narrow slit and then stick. He will never be able to pull himself back – at least until starvation has so reduced him that he will probably be unable, if set free, to win (as we say in Scotland) his way back to the open.’

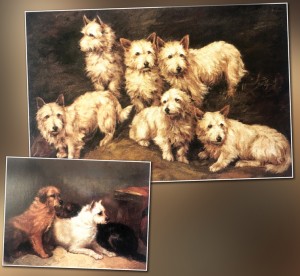

Many of the sporting families that worked these terriers preferred the colored dogs, brindles and reds, to the white, which they seem to have considered weaker and those that appeared in ‘normal’ colored litters were often quickly dispatched in the bucket. It was quite clearly a mistaken prejudice.

Thankfully, one or two families kept them segregated and then went on to selectively breed for the color.

These little dogs were seriously tough!

The Macleods of Drynoch were among those who gave preference to the whites, creams and sandies. In 1900, Mrs. Cameron-Head of Inverailort was among one of the very first to champion the cause of the West Highland White Terrier. Her maternal grandmother, a daughter of Norman Macleod, was born in 1800, and she used to relate how her father and grandfather kept the whites and sandies for sport, and that the whites were also kept for household pets.

And, as I wrote earlier, their fame was legendary and stretched quite far back.

Towards the end of his reign, James I writes to have half a dozen ‘earth dogges or terrieres’ sent carefully to France as a present, and he directs that they ‘be got from Argyll and sent over in two or more ships lest they should get harm by the way.’

This was four hundred years ago and it is highly unlikely that the King would have thought quite so highly of a newly created strain of ‘terrieres’ from Argyll.

With the booming interest in pedigree dog showing and breeding in Victorian times, an eye was soon cast on these small, short-legged terriers that had abounded for hundreds of years working in the Scottish Highlands. Records show that the breed was first scheduled at the annual show of the Scottish Kennel Club held at Waverley Market, Edinburgh in 1904, but this distinctive little terrier had actually been exhibited long before that under various regional names.

Poltalloch, Roseneath, White Scottish, Cairn and Little Skye had all been used by the breed until, in 1904, all the regional names were supplanted by ‘West Highland White Terrier.’

And, in the following year, the breed clubs in Scotland and England were formed, to be quickly followed by the USA and Canada (in 1909 and 1911) respectively.

The first of the breed to become an American champion was the English-bred ‘Clonmel Cream of the Skies’, bred by the famous Holland Buckley, one of the greatest authorities on the breed in the very early days.

The first of the breed to become an American champion was the English-bred ‘Clonmel Cream of the Skies’, bred by the famous Holland Buckley, one of the greatest authorities on the breed in the very early days.

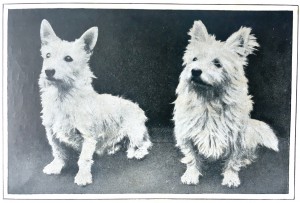

At the next Scottish Kennel Club Show, held in October 1905, ‘Morven’ won the Championship certificate and, in 1907, became the first champion in the breed. The Westie had truly arrived!

The first champion was highly regarded and did great service at stud.

D. Mary Dennis (owner of the world famous Branston kennel) wrote about Morven and his sire, Brogach.

‘Brogach has been described in some books as being a biggish terrier with great bone and substance generally, yet weighing only 17lb. I can find no record of the weight of Morven, who was stated to be smaller than his sire. It is also recorded that Athol, reputed to be Morven’s best son, weighed 16lb., and Ch. Glenmohr Model, the son of Athol, also weighed 16lb.

Also, in 1907, (alongside Ch. Morven) Ch. Cromar Snowflake and Ch. Oronsay, both gained their titles and were owned by the Countess of Aberdeen.’

So, 1907 was quite a significant year for the Westie, with its first three champions being produced and, these together with their contemporaries, laid the foundation for the breed we know and love today.

Appreciation from American dog fanciers came early for the Westie and they were soon eagerly buying up quality stock. Ch. Kiltie (after winning seven championships) was sold to America for the then record price of £420 – equivalent to roughly $55,000 today. Breeders in the UK were soon bemoaning the loss of yet another great dog who they claimed would have been ‘useful for the breed to retain’ but Glenmohr Model quickly followed Ch. Kiltie across the pond for the sum of £200. Then in the Stud Book for 1913 we get the entry, Wolvey MacNab. Now, I have never owned a Westie or had any rea

Then in the Stud Book for 1913 we get the entry, Wolvey MacNab. Now, I have never owned a Westie or had any rea

l association with the breed but from a young age I had heard the legendary kennel name, ‘Wolvey,’ and knew that it meant top quality West Highland White terriers.

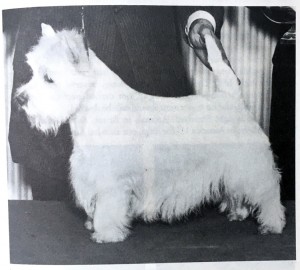

Its owner, Mrs. C. Pacey, was a breeder of exceptional ability and her espousal of the breed led to important consequences. Between the two wars, Mrs. Pacey kept the breed before the public. She succeeded in producing dogs with a ‘winning personality’ which enabled some to win Best in Show. When war broke out, realizing that constraints would be placed upon showing in the UK for quite some time, Mrs. Pacey sold her beautiful dog, Ch. Wolvey Pattern to Mrs. J.G. Winant. The little dog marked his arrival in a new country by becoming Supreme Champion at Westminster in 1942.

She had previously imported ‘Ch. Ray of Rushmoor’ to her Edgerstoune kennel where he sired ten champions. Later many of the best Wolvey champions bred by Mrs. Pacey went to the U.S. to join the Edgerstounes.

The Wolveys can also be found behind ‘Rachelwood’ – another famous U.S. kennel that produced many home grown champions.

The Westie quickly became view-ed as the consummate showdog, a far cry from his beginnings fighting vermin among the tight cracks and crevices in boulder strewn Argyllshire.

Snow white, with beady black eyes and nose, it’s a role he carries off with considerable aplomb and West Highland Whites have taken top honors at Crufts three times; Ch. Dianthus Button in 1976, Ch. Olac Moon Pilot in 1990 (a win I well remember watching) and, more recently, in 2016 when Ch. Burneze Geordie Girl won the top honors.

It’s a similar story in the states where West Highland White Terriers have featured as BIS winners at Westminster twice; Ch. Wolvey Pattern of Edgerstoune in 1942 and Ch. Elfinbrook Simon in 1962.

Sadly, along with such wins and the ensuing media exposure came the inevitable attention from the puppy mills and farms, and here in the UK, any small (and some not too small!) white terrier-like dog is often erroneously called a Westie by the general public.

Not much thought nowadays seems to be given to the Westie’s humble beginnings (the sporting breed, full of pluck that still lies beneath the carefully groomed eye-catching exterior) which is why I was particularly impressed with the West Highland White Terrier Club of America’s initiatives to keep alive the breed’s hunting instincts and to fully test them with ‘barn hunts’ and ‘earth dog’ trials. This is surely the way forward for so many pedigree breeds. How can we claim our dogs are really ‘fit for function’ if they are never tested?

Wouldn’t it be good if all our show dogs had to undergo such tests? Surely this would be one way to weed out the excessive and open coats, size issues, shyness, the lack of muscle, faulty temperaments and a multitude of other problems that still don’t seem to thwart a number of dogs on their trajectory to the very top.

The Colonel wrote these words back in 1907;

The Colonel wrote these words back in 1907;

‘I therefore earnestly hope that no fancy will arise about these dogs which will make them less hardy, less wise, less companionable, less active or less desperate fighters underground than they are at present.’

And in 2019 at least there are some who are working hard to make sure his fears for this breed (once described as being as Scottish as the Bagpipes) don’t become a widespread reality.

290 – August 2019

Short URL: https://caninechronicle.com/?p=168078

Comments are closed