The English Setter – America’s Oldest Gundog

Click here to read the full article in our digital edition.

From the archives of The Canine Chronicle, June, 2014

By Amy Fernandez

The Pointer has come to symbolize the foundation of America’s purebred dog world. It’s generally regarded as the breed responsible for setting the wheels in motion for key developments like national registries, formal shows and field trials, and years later, the founding of AKC. However, the English Setter may actually deserve this honor. It is America’s oldest Gundog and its skyrocketing popularity in post-Civil War America catalyzed the creation of every aspect of the sport.

Multiple factors contributed to America’s bull market for English Setters, primarily the resurgent postwar economy. Sport hunting had been on hold throughout the conflict, resulting in a wildlife population explosion. “Game is more abundant in this country than it ever was known before. The woods are literally filled with bear, deer, and turkeys, while our lakes and bayous are swarming with ducks and geese.” (The Osceola Times, Oct. 22, 1870)

Multiple factors contributed to America’s bull market for English Setters, primarily the resurgent postwar economy. Sport hunting had been on hold throughout the conflict, resulting in a wildlife population explosion. “Game is more abundant in this country than it ever was known before. The woods are literally filled with bear, deer, and turkeys, while our lakes and bayous are swarming with ducks and geese.” (The Osceola Times, Oct. 22, 1870)

This combination of leisure time and plentiful game attracted waves of new converts to the sport and spawned a host of related enterprises like tourism, as described in Wayne Capooth’s 2001 book, The Golden Age of Waterfowling. “The railroad offered a special rate to hunting parties of three or more. One hundred and fifty pounds of baggage, including guns and dogs, were carried free of charge. For larger parties, hunting cars with sleeping quarters for about thirty were chartered.” Along with western adventures and expensive shotguns, Americans developed quite a hankering for purebred, imported Gundogs.

At the time, purebred lines were the exception rather than the rule in America, as Joseph Graham noted in The Sporting Dog in 1904. “For generations before the Civil War – that period coinciding with the establishment of field trials and regular records in England –?both setters and pointers had been brought over at frequent intervals and had left progeny from Maine to Florida as far as enterprising field shots had penetrated…if a man wanted to breed setters, he seldom did more than use the best stock in the neighborhood.” Generations of interbreeding produced countless regional strains. Known as Native Setters, they were plentiful, functional, well adapted to local game, and abruptly out of fashion.

Many factors fueled the resultant demand for imports, none more than the archetypical lure of the status symbol. It took on new significance in this case thanks to field trials. This newly-introduced British sport provided the first measurable quality standard, which completely revised perceptions about Gundogs. In America, “field trials quickly followed the importation of winning English pointers and setters.” Graham described early entries as, “a miscellaneous lot, which would excite amusement if they appeared before latterday judges. Irish, Gordon, crossbred, and native English Setters, many of them pet shooting dogs.”

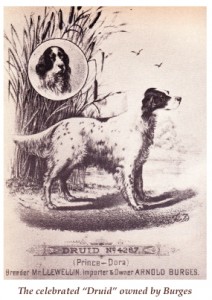

Thanks to Arnold Burges, we have a record of some of them. During his career, Burges wrote for almost every major sporting journal. But he earned his historical moniker “Father of the American Studbook” for his groundbreaking 1876 work The American Kennel and Sporting Field. It documented 327 Gundogs, primarily English Setters. On March 31, 1888 American Field summed up his contributions saying, “He was among the first to advocate improving American sporting dogs by importation from the best kennels in Europe… it was not long before he became a recognized authority on all subjects pertaining to field sports.”

Of course, that couldn’t happen until America had field sports. That’s where Dr. Nicholas Rowe entered the picture. Rowe has variously been described as an idealistic crusader or a predatory opportunist. Four years younger than Burges, their career trajectories were remarkably similar. Rowe embarked on a medical career until his Gundog obsession overshadowed his professional aspirations. An advantageous marriage allowed him to pursue his passions. He began breeding Gordon Setters and Irish Setters. In 1872 he settled on English Setters and imported steadily throughout the decade.

Of course, that couldn’t happen until America had field sports. That’s where Dr. Nicholas Rowe entered the picture. Rowe has variously been described as an idealistic crusader or a predatory opportunist. Four years younger than Burges, their career trajectories were remarkably similar. Rowe embarked on a medical career until his Gundog obsession overshadowed his professional aspirations. An advantageous marriage allowed him to pursue his passions. He began breeding Gordon Setters and Irish Setters. In 1872 he settled on English Setters and imported steadily throughout the decade.

Like Burges, he contributed to most of the era’s sporting journals. His prolific output assured his prominence in America’s burgeoning dog game. According to the AKC Gazette, May 1972, “Rowe’s interest in all sorts of matches and field trials was intense and his knowledge as to how they should be conducted was extensive. For these reasons, his efforts towards regulatory guidance became ‘the law’. When a committee was in doubt, they generally found it best to ‘ask Dr. Rowe’.”

He is credited as a primary organizer and principal financial backer of America’s first successful bench show held October 7, 1874 in Mineola. Held in conjunction with the Queens County Agricultural Fair, its miniscule entry of Pointers and Setters were judged according to Kennel Club rules. He also helped to launch the first successful field trial held outside of Memphis one day later.

Attempts to establish bench and field sports commenced soon after they debuted in Britain. Unfortunately, most were unsuccessful. Among those condemned to failure for disorganized judging and weak entries were the Illinois State Sportsmen’s Association of Chicago on June 2, 1874 and the New York State’s Sportsman’s event on June 22. On Oct. 8 the Tennessee State Sportsmen’s Association sponsored America’s second bench show combined with its first field trial outside of Memphis. Compared to the previous events, its entry of nine Pointers and Setters qualified as a resounding success. Even though the winner was a native-bred Setter, it fueled the emerging interest in imports. The group’s next event in October 1875 was judged by Rowe and his close associate, Major James Taylor. The Tennessee State Sportsmen’s Association retained a monopoly on field trials for the next three years. Meanwhile, bench shows of varying success took place in Michigan, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont throughout 1875.

Burges documented the evolution of America’s dog game, but Rowe realized it would never achieve sustained momentum without an organized infrastructure. And his gregarious, blatantly ambitious nature made him ideal for that job. His big career break came in 1876. He took over as editor of The Field. He relocated to Chicago and immediately organized an American version of Britain’s three year old Kennel Club. On January 26, 1876 he became first president of the National American Kennel Club. Burges served on the board, and like the other officers, field trials were their overwhelming priority.

Of course, Rowe’s main agenda was The Field. In short order, he revamped this modest Midwestern weekly, drastically refocusing its editorial content to cultivate interest in purebreds and dog sports. Within three years, circulation and advertising revenue skyrocketed. It was renamed Chicago Field in 1879 and morphed into American Field two years later. Now America’s oldest sporting journal, it’s a priceless record of this seminal era.

On March 11, 1876, The Field presented its free field trial registry service. A few months later on August 26, 1876 the National American Kennel Club announced plans to publish a studbook and regulations for bench shows and field trials. America’s purebred scene was picking up steam when Westminster’s triumphant 1877 inaugural show hit it like a shot of adrenaline. The pieces fell into place from there, but none of it happened as easily as this appears in retrospect. The sheer size of this country posed challenges to any national effort. A very small group was responsible for launching and sustaining every facet of this monumental task.

Ironically, less than a century earlier, English Setters barely qualified as an established breed. A conglomeration of regional strains were customarily intermixed and/or crossed to Spaniel or Pointer to enhance functionality. In his 1950 overview of Setter evolution in Dogs Since 1900, Croxton Smith credits one breeder for revising this free and easy approach, Edward Lavarack. Lavarack was a shoemaker’s apprentice back in 1825 when an unexpected inheritance abruptly revised his career plans. His subsequent contribution to Setter development has been recounted by countless historians. Watson weighed in on the subject in 1903 for The Dog Book, “His knowledge of the Setter dated from early in the last century, for he was shooting in the Highlands when he was eighteen…and must have had personal knowledge of Setters from 1815.” Lavarack used his windfall to splurge on a pair of first-class shooting dogs. Ponto and Old Moll were approximately two years old and the best money could buy. He mentioned the source of his foundation dogs only in passing. Later historians followed suit, but Watson noted that they came from Reverend A. Harrison. “He had kept his strain for 35 years and carefully guarded their breeding all that time.” Even so, Watson speculated that he probably had “no thought of what he subsequently went in for in breeding.” But Lavarack certainly did go in for breeding.

He developed an exceptionally consistent, tightly bred strain. Its impact on English Setter development cannot be overestimated. In Twentieth Century Dog Herbert Compton said, “When he died 30 years ago, he left only five dogs, but the blood of those five animals is diffused through a great number of present day winners; in America, where he exported several specimens from his kennels, a magnificent breed of setters has been propagated from his stock.” By then, Lavarak’s line represented over a century of cumulative selective breeding.

The first pair of Lavaracks arrived in America in 1874. Watson called them “thorough gundogs, caring little for anything save seeking and finding game”, adding that they were strictly shooting dogs, never run in trials. Word got around anyway and by 1881, his bloodline was represented by 46 descendants of this pair, along with ten more imports. Its ongoing success is amazing because the Lavarack line endured quite a beating from the next generation of English Setter fanciers.

After Lavarack died in 1877, Croxton Smith dramatically reported that, “the mantle fell upon the shoulders of Mr. R. Purcell Llewellin …Some consider his influence on the family more beneficial than that of his great predecessor.” This tidy, official version of events has been consistently confirmed by countless Setter historians like Mrs. Ingle Beppler in 1937. “The development of the modern English Setter is mainly due to the untiring efforts of the late Mr. Edward Laverack… what he began Mr. Purcell Llewellin perfected.” However, like most dog breeding, the real story was far more complicated and messy. Some contemporary sources offered dramatically different accounts of what went on in Setters back then.

Lavarack’s status as a respected authority got a bit more luster after the publication of his book, The Setter, in 1872. His protégé also got a nod in the dedication, “to R.L. Purcell Llewellin, Esq. of Pembrokeshire, South Wales who has endeavored and is still endeavoring, by sparing neither expense nor trouble, to bring to perfection the Setter.”

Before headlining in English Setters, Llewellin had started in Gordons in 1860, switched to Irish, and experimentally crossbred them, which was fairly standard practice. Efforts to better adapt Setters for the rapidly changing demands of sport hunting were well underway by 1865 when field trials added another element to the challenge.

Llewellin was far from the first or only breeder venturing down that path, although some authorities, like Stonehenge, described him as floundering around desperately trying different combinations when he hit on one that changed his fortunes.

The breeding formula later dubbed the Duke-Rhobe-Lavarack combination was already popular in 1871when Llewellin purchased Dora, Dick, and Dan. These littermates were sired by Barclay Field’s Duke, a black and white dog bred from a variety of local Setter strains. Their dam, Statter’s Rhobe, was a heavily marked bitch descended from both English and Gordon stock. Llewellin called her long, low, heavy, and slow. Neither of them qualified as a superstar. However, crossing their get back to pure Lavarack was the closest thing to a sure bet that’s likely to happen in dog breeding. The success of this unconventional recipe was a classic nick. Most importantly, the resulting quality carried through subsequent generations.

Llewellin also purchased several Lavaracks, most notably the littermates Countess and Nellie who earned distinguished field trial records. Like others, he had success breeding from this combination. However, the magnitude of that success is hard to gauge. Some sources described him rocketing to the top in both bench and field competition. “It is no exaggeration to say that this gentleman’s Setters, greatly successful as they were on the bench, were practically invincible in the field. At the Birmingham Show in 1884, Mr. Llwellin entered 12 Field Trial winners, several of them being bench champions as well.” Beppler was far from the only writer to emphasize Llewellin’s domination, but others like Graham categorized it as modest. “Mr. Llewellin is known there merely as one of a large number of gentlemen who have had successful kennels of English Setters; it is well to state that field trials in England are comparatively small and never had anything resembling the relative prestige and influence they have won in America.”

Either way, Llewellin stock started trending in America. It’s fair to say that Lavarack dogs intensified interest in British lines and the first Llewellins arrived a few months later. “His first exports to America triggered a craze for ‘blue blood’ Llewellins.” In 1949, Henry Davis described it as insatiable in The Modern Dog Encyclopedia, attributing it to their “general excellence in field performance, coupled with a well planned advertising campaign.”

Watson made the same allegation 50 years earlier, “ They were exciting very little attention in England compared to the agitation in the American press… even Shaw, writing in 1880, gives no intimation that Mr. Llewellin had ‘set the Thames on fire’ with his world beaters.” And decades before Watson, Stonehenge flatly dismissed Llewellin’s budding fame in the 1877 edition of Dogs of the British Isles. Moreover, he personally saw most of the era’s field trial dogs, including Duke, Rhobe, Dick and Dan. “I come now to consider the value of Mr. Llewellin’s ‘field trial’ strain, as they are somewhat grandiloquently termed by their ‘promoters’ or as I shall term them, the Dan Laveracks… as far as I have seen them perform, they have not proved themselves to be above average.”

The competitive accomplishments of Llewellin imports may not have been big news their homeland, but they were impressive in America, which had nothing comparable at the time. But Stonehenge alluded to something a bit more alarming than varying perceptions of quality. “Upholders of the Llewellins were not as accurate as they should have been.” Specifically, the American writer “Setter” wrote of vastly inflating show records of Llewellin imports and their progeny. Setter, of course, was the pen name used by Burges. Rowe sometimes editorialized as “Mohawk”, but was generally happy to take credit for his share of “agitations in the American press.” Although his term as president National American Kennel Club ended in 1878, he remained front and center of America’s emerging dog scene. In fact, every member of the Llewellin clique quickly ascended to the top.

From a modern perspective, the pervasive conflict of interest reflected in each of their careers seems astonishing. In reality, this rather incestuous arrangement was almost inevitable because it was “on the job training” for everyone involved in the sport back then. Consequently, they earned recognition as experts simply because they got in on the ground floor and had the most experience in every aspect of the game. In 1891, The Stockeeper described the resulting situation, “The power of Westminster began to be felt, and as that show was the largest, they were soon consulted by smaller clubs as to who should superintend and judge the dogs.”

Kentucky native Major James Taylor, who had helped to organize the historic Memphis field trial, may be best remembered for his book, Field Trial Record of Dogs in America, one of his many achievements. His early association with Llewellins assured his reputation as a purebred dog authority, which translated into ongoing success as a major breeder, broker, importer, and judge – before, during, and after his rather unimpressive tenure as AKC’s first president. Another of Rowe’s associates, Elliot Smith, served as AKC’s first vice president under Taylor and subsequently took over for him. He was a member of Westminster from 1880-97, managed the club’s legal matters, hosted meetings at his Wall Street office, and served as its first AKC delegate. Throughout those years he also bred, imported, brokered, and judged.

Westminster charter member and first show manager, William Tileston, arrived in New York to become the editor of Forest and Stream. In 1878 he quit his day job and devoted himself exclusively to the dog business, breeding, brokering, importing, and managing shows. For someone with a wife, four kids, and a mortgage, that might have seemed like an irresponsible career move. In reality, it was financially sound and well-calculated. Ironically, it did turn out to be a risky venture for poor Tileston thanks to a fatal construction accident shortly before Westminster 1881.

The club’s first superintendent, Charles Lincoln, was possibly the biggest player at this stage. His prior experience managing British shows catapulted him to the forefront in America. Along with importing and brokering, his lucrative multifaceted career put him in the catbird seat to call the shots for almost everything that required an expert opinion or endorsement. His successor, James Mortimer, began as Westminster’s kennel manger. He was equally famed as a judge, importer/broker, and professional show superintendent.

Like others, Rowe was ideally placed to cash in on the Llewellin craze. In addition to earning a tidy sum breeding Llewellin stock, it became the linchpin of his far reaching success. He understood the concerns and challenges of America’s growing number of Gundog fans, and American Field became their indispensable resource. He freely utilized it to promote key concepts to a national audience, as shown by this November 17, 1883 editorial. “Men admit the importance of blood, pay out money in the effort to get it, yet have so little knowledge that they do not know the limitations of strains and have not the means of knowing whether what they buy is pure article or not. […] Dogs are advertised and sold continually under false pedigrees and the evil results, small at first, are rapidly increasing […] finely bred dogs are now as eagerly sought after by true sportsmen as finely built guns. No man would like to have it proved that his gun has not the right to its name; neither would he like to have a flaw in his dog’s pedigree detected. There is not probably any other matter upon which the average sportsman has so little knowledge as upon pedigrees, yet there is hardly one more important.”

This group’s experience and unofficially designated authority also made them the default gatekeepers. Rowe utilized his insider’s knowledge and journalistic censure to promote concepts for the overall good of the sport and defend the coalescing arrangement.

Perhaps their efforts were not completely altruistic, but no American showcase existed to promote Llewellins – or any breed – until someone established bench and field sports and an official system to document lineage and accomplishments. Long before these measures were in place, the escalating demand for purebreds invited opportunism and fraud in America’s virtually unregulated dog world. Llewellin promoters had a vested interest in policing the process, comparable to preventing competition posed by designer knockoffs.

A national registry was simply a means of protecting the status quo. Possibly, it was an unintended consequence but as Davis notes, Llewellin fans became obsessed with pedigrees. “It is a fact that the period when preference for the Llewellin strain bordered on the fanatic and many Setter breeders paid far more attention to pedigrees than the field performance and qualities of the dogs.”

Many critics contended that an actual Llewellin bloodline didn’t exist when its reputation was launched. Llewellin had worked with the Duke/Rhobe/Lavarack combination less than five years when the fruit of his labors began arriving in America. Descriptions confirm that they were a varied lot, reflecting their diverse heritage. Graham called it “mere pretense” to treat them as an established strain. From that standpoint, pedigree would have been the single identifying feature that could be utilized to build a brand. And both bench and field fanciers flocked to the Llewellin brand.

Watson and Hochwalt, quoted here, weren’t alone in noting that Rowe’s association with American Field dovetailed with the Llewellin Setter’s almost instantaneous fame. “The lavish use of printers ink by the commercial clique who had the interests of this strain in hand, prevailed at last and a name which was primarily used to advertise dogs from the kennels of Llewellin was finally foisted upon the American public s representing a distinct breed of Setter, of which he was the originator. Here in America, usage had given the name a definite sanction, in England, however, even at this date, there is no such breed as Llewellin Setter.”

Today, it’s accepted that fame breeds its own success. Maybe the precise definition of a Llewellin was ambiguous, their bench and field accomplishments might have been questionable, and Llewellin’s motives open to interpretation. But it’s apparent that he was ahead of his time. Because if you build it they will come, and they did. Eventually, Llewellin’s reputation was enough to signify actual achievement. Even so, Gundog historians still debate the circumstances Llewellin’s start in America. Although most of it has been endlessly rehashed and reexamined, one significant detail has been shortchanged by the historical record.

Llewellin’s handler/trainer/kennel manager/cousin Teasdale Bucknell, oversaw most details for his international sales. And back then, this required the archaic process of exchanging letters. He was quite a chatty guy and much of his correspondence was preserved. It included numerous bombshell admissions of the insider’s deal cooked up with major Llewellin promoters in America. Strict historians have dismissed Bucknell’s contentions of fraud and collusion as hearsay, but we’ve got another clue straight from the horse’s mouth – or Mohawk’s pen to be precise.

By 1883, America was enamored with everything Llewellin, so it’s understandable that Rowe set his sights higher. He announced plans to send some of his Llewellin-bred pups to compete at English field trials. The highly publicized fanfare was premature because it didn’t go well. Rowe was not a gracious loser, and his impulsive nature got the best of him. In 1884, Llewellin’s premier champion, Dr. Nicholas Rowe, abruptly and remarkably reconsidered his opinion. This vindictive grudge got primetime coverage in American Field. Watson poured over every salacious detail, noting something that’s never lost its relevance in the dog world. A bad dog deal is like a derailed love affair. “To paraphrase a well-known proverb, when fanciers fall out, we are apt to hear some honest truths.” Watson called it, “quite a wordy warfare”. In a long series of vitriolic editorials, “the Doctor uncorked himself and told more real truths about the Llewellin business than has appeared in that paper since then.” He remains the only historian to extensively document this fascinating, long-forgotten episode in purebred history.

The source of the term Llewellin was an ongoing controversial issue. His first imports came labeled rather generically, as a field trial strain. Subsequently rechristening them as Llewellins was variously explained a concession to generally accepted terminology, a popular desire to honor the line’s originator, or savvy marketing. Rowe attempted to shift the blame to Burges, Bucknell, and Llewellin, claiming that he simply went along with them. “The dogs were not then popular (1878) excepting among a few who owned them, consequently there were not those who, although they ridiculed the idea, yet took sufficient interest in the matter to oppose it quickly. The title therefore came into use, and we used it the same as we do many other vulgarisms.” (American Field April 26, 1884)

Regardless of how it went down, Watson emphasized that the NAKC registry sealed the deal when it granted Llewellins designation as a separate breed. “To this day, the American Field is the staunchest supporter of the Llewellin Cult and in the studbook which it publishes annually, there is a section entitled Llewellin Setters to distinguish it from English Setters,” adding that the NAKC could have easily revised that status, but that never happened.

Rowe also described a calculated plan to highjack Lavarack’s reputation. Needless to say, Llewellin couldn’t manufacture the decades of work and success that had made his mentor’s name ubiquitous and respected. According to Rowe, he remedied that by commandeering credit for everything descended from Duke/Rhobe or Dan/Lavarack pedigrees. Despite the fact that he didn’t originate this combination or breed most of the dogs derived from it, they became classified as Llewellins.

Over time, the definition of a Llewellin certainly broadened, and the first volume of the NAKC studbook suggests that it was intentional from the start. Rowe documented many of the same dogs that Burges included in his 1876 English Setter records…with some revisions. For example, the first dog recorded in both studbooks, Adonis, was subsequently registered by NAKC with a Llewellin sire and dam. Rowe also zeroed in on Burges’s centerpiece Llewellin, Ch. Rob Roy, “A dog that Llewellin didn’t breed, never owned, whose ancestors he never owned or bred.” Of course, this dustup didn’t change the fact that Rob Roy wasn’t purebred by any stretch. By Fred out of Rhobe, at best he was crossbred English and Gordon, a fact overlooked by these staunch supporters of purebred pedigreed lineage.

Regardless of who hatched the plan, a deception of that scale could never have gained traction without the complicity of everyone in this group. And that would have been impossible without the concurrence of their self-appointed watchdog, Dr. Nicholas Rowe.

The trajectory of English Setter judging remains the best circumstantial evidence to illustrate Rowe’s journalistic manipulation via his firebrand rants. When American Field didn’t agree with a judge, his decisions were mercilessly shredded in post-show editorials.

In his book, Watson detailed the extent of this heavy handed influence. “The glamour of the field trial performances of certain dogs twisted Setter judging to such an extent that Lavaracks became practically extinct….the fact that a dog was descended from parents of excellent field qualifications was evidently ample reason for placing that dog high in the prize list…..the same methods were adopted in field trials…until it was almost a necessity to run dogs of certain breeding to win.” Every breed suffers from occasional episodes of erratic judging, but in this case, it completely derailed English Setter type. According to Watson, it began to regain balance in 1898, but it required almost two generations to repair the damage.

That could never be good news for Setter lovers, but worse harm surfaced in the wake of this fad. Many members of this Llewellin gang laid the groundwork for AKC. And the first skirmish on that front centered on its organization as a club of clubs or the traditional arrangement of a club of members. America ended up with the more cumbersome “club of clubs” thanks to this dominant clique, and it’s plain that self-interest was the bottom line. Back then, it virtually barred small or distant clubs from participating in policymaking. For decades, that power was confined to delegates near New York who usually became proxies for the rest of the dog world.

However, in the long run, the dictatorial nature of this arrangement also balanced out. And today, its self-limiting voting power has become an excellent safety feature. AKC decisions will never be totally democratic, but the limited voting rights and complex club approval system virtually prevents voting fraud or power block takeovers. Maybe that wasn’t the goal of AKC founders, but Americans have far more voice in the process than other national kennel clubs – especially the Kennel Club.

Short URL: https://caninechronicle.com/?p=51920

Comments are closed