Looking Back · Down In Flames – The William MacKay Story

Click here to read the complete article

118 – November/December, 2014

By Amy Fernandez

“Principles like quality, integrity, and sportsmanship were being abandoned like excess baggage in this relay race for new records.”

Even if you didn’t live through it, the 1980s conjures up vivid social concepts, first and foremost, hedonism and conspicuous consumption. Tax and business reforms heralded an era that was destined to recapture the best of America’s entrepreneurial spirit. Unfortunately, the lack of restraints also unleashed the downside of that business model. No one said it better than Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street. “Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right. Greed works. Greed clarifies and cuts through to the essence of the evolutionary spirit.” Innovative technology like cell phones and home computers added a new dimension to the decade’s endless shopping binge. But reckless avarice wasn’t limited to consumer goods. Amassing money, power, and fame became a game in itself.

As always, predominant social trends permeated America’s dog game. Over at AKC it triggered a bull market. Every facet of the sport skyrocketed. AKC experienced the biggest influx of new exhibitors since the ‘50s. In 1981, for the first time, over a million dogs competed at AKC events. Registrations spiked, as did the size and number of shows, which topped 1000 for the first time in 1985. All this translated into an endless string of achievements as unprecedented numbers of dogs set and broke new records. The 100 Best In Show barrier began to seem like a routine accomplishment. The next step was that unimaginable possibility of 200 Best In Shows, which fell to Ch. Braeburn’s Close Encounter by the middle of the decade.

They should have been doing the happy dance over at 51 Madison Avenue. Oddly, that wasn’t the case. Some troubling issues began to suggest that phenomenal growth wasn’t indicative of overall health. For instance, SEVEN dogs garnered over half of 1987’s group and BIS wins. As usual, this was an ongoing topic among exhibitors long before AKC caught the buzz and began to examine unsettling trends emerging in the sport. There was a collective sense that something was amiss. They cited factors like the proliferation of cluster shows and legions of inexperienced novices knocking around the game but couldn’t pinpoint the real issue. Specifically, principles like quality, integrity, and sportsmanship were being abandoned like excess baggage in this relay race for new records.

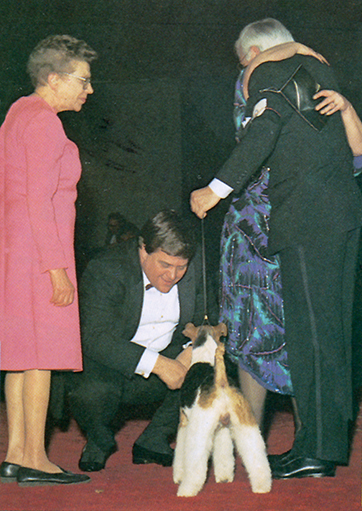

The first unsettling glimpse behind the curtain of that fabulous era came with the sordid demise of Alan Novick, the owner of Ch. Braeburn’s Close Encounter, on November 23, 1984. It was soon followed by the notorious “MacKay Affair.” The dog at the center of this scandal was the Wire Fox Terrier, Irish/English/American Ch. Galsul Excellence, co-owned by William MacKay of Bellmead, New Jersey and Ruth Cooper of Glenville, Illinois. Handled by Peter Green, Paddy ranked as America’s top dog for 1986-87. He earned 103 Best In Shows before his career came to an abrupt, unsavory end along with MacKay’s personal and professional downfall. And he had plenty of company when he went down in flames.

MacKay’s road to wealth seemed like a classic American success story. It began in 1973 when he embarked on a career as a medical supply salesman. He met his wife, Joyce, while pitching orthopedic products at Long Island’s Smithtown Hospital where she was a surgical nurse. They married in 1975 and devoted themselves to raising six children and running their new home-based medical supply business. It thrived but money was always tight. MacKay attempted to remedy this by launching a series of unsuccessful ventures throughout the ‘70s. He also entered the dog game around this time. Like many before him, his passion for horses led to his interest in dogs. He began breeding and showing Dobermans under the Kaymac prefix.

MacKay’s road to wealth seemed like a classic American success story. It began in 1973 when he embarked on a career as a medical supply salesman. He met his wife, Joyce, while pitching orthopedic products at Long Island’s Smithtown Hospital where she was a surgical nurse. They married in 1975 and devoted themselves to raising six children and running their new home-based medical supply business. It thrived but money was always tight. MacKay attempted to remedy this by launching a series of unsuccessful ventures throughout the ‘70s. He also entered the dog game around this time. Like many before him, his passion for horses led to his interest in dogs. He began breeding and showing Dobermans under the Kaymac prefix.

In 1983 MacKay’s determination finally paid off. A year earlier he had become a sales consultant for American Biomaterials, a biotech startup that planned to market an artificial bone substance called Bioglass. Despite his lackluster work history and eighth grade education, MacKay ascended to CEO of American BioMaterials whose subsequent initial public offering netted millions for him. The family soon relocated to a six bedroom house on four acres in Belle Mead, New Jersey newly outfitted with luxuries like a 25 run kennel, Olympic-sized pool, Jacuzzi, a new Mercedes and $100,000 dog show bus. Only one thing was missing from MacKay’s dream. He desperately wanted to join that rarefied world of jetsetting, dog show celebrities. Of course, that required an invincible dog. He soon broadened his search beyond Dobermans and America’s dog show scene.

Whelped March 5, 1983, Paddy heralded from John Galvin’s famed Galsul kennel in Ireland. First shown at East of England on July 7, 1984, he won Junior Dog. The judge’s subsequent report was complimentary and prophetic, “Give him another couple of months and he will be pressing for top honors.” A few months later at his next show, the Wire Fox Terrier Association specialty, he went Breed for his first ticket. He easily earned his English and Irish titles along with growing appreciation for his soundness, style, and beautiful head. It was obvious that this marked him for greatness.

Nicole Chashoudian had a front row seat throughout Paddy’s interesting career. “He had a pedigree to die for. It was so elegant.” Sired by English Ch. Harwire Helmsman of Whinlatter out of Galsul Institution, his potential contribution as a sire seemed immense. However, that wasn’t the primary motive for bringing him to America. Wires have never suffered a shortage of superstars, but 1983 was a banner year. At that time, Britain’s dog world grapevine was buzzing about two equally fabulous young dogs. Ch. Sylair Special Edition traded wins with Paddy until their final showdown at Crufts 1985. Neither contender triumphed but ‘George’ was snatched up by Ric Chashoudian and headed to America.

Special Edition’s blockbuster American show career seemed like a foregone conclusion. Only one dog had the potential to challenge that supremacy. A few weeks later, MacKay provided Peter Green with a check for $15,000 and sent him over for Paddy who would be co-owned and campaigned by MacKay and Ruth Cooper. Oddly, neither one of them thought to look beyond MacKay’s Baroque lifestyle before embarking on this deal. A superficial background check or glance at his controversial 1978 book would have revealed countless red flags. His eclectic career history had one common denominator. Every venture soon ended in failure and cheated business associates. But the dog show world welcomes everyone and throughout its history, shady characters have easily found a niche in our show world.

Moreover, every aspect of this deal ran like a well-oiled machine. Paddy exceeded all expectations and MacKay’s deep pockets helped to move the project along at a lightning pace. By 1986, he had dominated the ring for 18 months. His 117 group wins that year set a new record. Over 50 percent of them resulted in Best In Shows, putting him at the top for 1986.

Life was good until the IRS came knocking. They finally noticed that American Biomaterials had stopped paying its quarterly taxes in 1984. Although MacKay and American Biomaterials CFO and treasurer, Muncie Russell, received salaries comparable to today’s CEO’s, that couldn’t support their newly lavish lifestyles. Company coffers overflowed thanks to McKay’s slick salesmanship that seems clearly illegal and immoral by today’s standards. Like most bad habits, occasional dips into company funds soon became a chronic pattern. That translated into 1984 operating losses of $1,751,233. In 1985 it jumped to $3,333,803, spiked to $7,374,226 in 1986, and they had helped themselves to $5,849,742 by July 31, 1987 when they were ousted during an overdue showdown with creditors and investors. Needless to say, none of them had investigated MacKay beforehand. After all, this was the ‘80s and no one wanted to miss out on golden opportunities to get rich.

Mr. Gerald Mauder took over as American Biomaterials CEO, and within a month he pieced together enough facts to discover why they weren’t paying their taxes. MacKay and Russell had emptied the piggy bank. The company filed for Chapter 11 on December 2, 1987 and the IRS filed a proof of claim for unpaid income and social security taxes on January 15, 1988. MacKay’s misdeeds qualified as much more than inept mismanagement. He faced both civil and criminal charges, but didn’t skip a beat. Along with his complete lack of restraint and penchant for unethical activities like embezzlement, MacKay had a pathological need for attention. Those personality traits are generally incompatible with a successful life of crime. If he had any sense, he would have stayed under the radar, but he was addicted to the fame that Paddy brought him.

The bankrupted firm filed civil suits to recover the stolen funds. In reality, Mauder couldn’t do much to repay defrauded investors, but he could get even.

No one was rejoicing over at 51 Madison Avenue by the time Westminster 1988 rolled around. Paddy had just ended his second year as America’s top dog when AKC announced that 48 Hours would produce a segment about the show, which meant there would be roving camera crews with full access. Among other priceless footage, they captured a treasure trove of illegal grooming practices as dogs were prepped. AKC ignored that blatant cheating along with a stunning display of bad sportsmanship inadvertently broadcast to millions of primetime viewers. Dog World columnist Herm David analyzed this problematic publicity the following month, “William MacKay was affable enough when he had the opportunity to brag about Ch. Galsul Excellence, who accumulated sufficient wins in 1987 to become Top Show Dog of the Year. When Excellence was defeated in the Westminster group, the well-briefed CBS team had a camera in position to record his reaction. His response was to put his hand over the lens.” There were also some additional offensive comments made to 48 Hours by members of MacKay’s team.

David’s inquiries about possible AKC disciplinary action elicited the mystifying noncommittal response, “they were weighing the matter. In reality, AKC didn’t know where to start dealing with the MacKay mess.” By November 1988, the dog world knew the story, which David attempted to clarify for his readers. “The recent MacKay affair focused attention upon the way in which AKC deals, or attempts to deal, with those it considers miscreants.” In this case, they seemed to be everywhere. David explained that, “those left in charge of American Biomaterials were so angry they furnished AKC with both quality and quantity of evidence. It was more than they had ever hoped to gather, even with its staff of investigators.”

The company’s books were a disaster, but MacKay had scrupulously declared his business expenses. AKC received a complete, detailed report documenting the astounding amount of company funds he had misdirected into his dog hobby. A quote from his self-congratulatory 1978 book highlighted the dubious ethics and insatiable greed that guided his life. He had found his niche as a salesman and he was unbeatable. He wrote, “Selling is a competitive, cutthroat business. The key is to sell your product. If you fail, financially speaking, you are dead. So, I sold as hard as I could and sometimes I made friends and sometimes I made enemies. It was all part of the game.”

In this case, that game included outright bribery. However, MacKay didn’t simply bribe judges; he put them onto the company payroll. Better yet, he paid himself to do it. Interesting revelations in MacKay’s business expenses included over $400,000 in fees to his personal executive recruitment firm that hired outside consultants and new employees.

Rumors about AKC’s impending actions began circulating in early January, 1988. In part, the resulting anxiety was prompted by their recent disclosure of 1987 expenditures, which included over a million dollars to defend themselves against damage suits from suspended individuals. AKC took no steps to alleviate the tension. For months, their only response was to repeat and rephrase their January 13 press release which said in part, “The American Kennel Club has always, in the past, investigated alleged acts of impropriety relating to the sport of purebred dogs. This effort is designed to preserve the integrity of the sport …AKC is currently conducting an investigation of alleged judging improprieties in connection with show wins and judging assignments …further information will not be released unless disciplinary action is taken.”

Meanwhile, in March the AKC Gazette began reporting the suspensions of three judges, beginning with John Staneck. MacKay’s Trial Board consisting of Basil H. Taylor Esq., Chairman, Roger Hartinger and Dennis Sprung convened June 7. The charges included accusations of MacKay conducting himself in a manner prejudicial to the best interests of purebred dogs, dog shows, and the AKC through direct and indirect actions in order to improperly influence and compromise the impartiality of numerous judges. His enticements were described as money, gratuities, services, or other considerations. There were claims MacKay engaged in a campaign of misinformation to impugn the reputation of certain judges who resisted his overtures. They recommended that he be suspended indefinitely with no reinstatement possible and be fined $10,000. MacKay failed to show for his July 6 hearing. He was found guilty as charged and forfeited his right to appeal. The process was concluded on September 13, 1988.

Click here to read the complete article

118 – November/December, 2014

Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=64309

Comments are closed