The Best Breed in The World? – The History of the ‘American Gentleman’ The Boston Terrier

Click here to read the complete article

116 – September 2019

Americans are sometimes, quite wrongly in my opinion, accused of being rather boastful folk, bragging that they have the ‘biggest this’ and the ‘very best of that’. However, if any American were to claim that their nation was responsible for creating the best breed of dog in the world, I as a proud Englishman would have to humbly concur.

Of course, at this point it is probably best that I admit my unashamed bias; I am the devoted owner (adoring slave) of two Boston Terriers and, although I have kept a number of breeds over the years (and regular readers of my work will know just how much I love my Dachshunds), no breed has ever come quite as close in my affections as my two ebullient Bostons, Lola and her daughter, Pebbles.

My two canine clowns have literally seen me through some very depressing and, quite often, dark times, and I owe so much to this ‘All American Breed’ for always making me smile when there was actually very little to smile about.

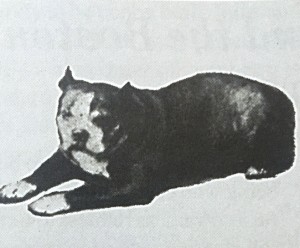

American? Most certainly…but the germ of this very special little dog can be traced back to England. Around the 1860s, crosses between the Bulldog and the English White Terrier were enormously popular. They were famous for their prowess as ratters and as fighters, and these dogs (which also displayed enormous intelligence) evidenced the very best features of their Bulldog AND terrier ancestry.

Some of these medium-sized, brindle and white dogs were carried on ships to Massachusetts, and immediately became a hit with dog fanciers in the Boston area.

One of the very earliest of these fanciers was Dr. James Boutelle who wrote about the very early days of the breed. Writing at the turn of the 20th Century, he gave a fascinating account of the Boston’s beginnings:

‘There are many people who claim to ‘be in on the ground floor’ in the production of these terriers, but to Mr. John P. Barnard Jr., of Boston, Mass., the credit is mostly, if not entirely, due. Over fifty years ago one of the most famous hack stables belonging to the John. P. Barnard Syndicate was situated on Myrtle Street. This was the headquarters for nearly everyone ‘doggy inclined’ in the city. John P. Jr. had in his employ the late Tom Thornton, acknowledged as one of the leading authorities on Pit Dogs of his day. Over the office, on the second floor, Mr. Barnard had a nicely arranged kennel, and the walls were covered with prints and photos of all the leading canines of both countries. Truly it was a treat for the eyes to look them over. In his kennel pens were thoroughbred Bulldogs and Bull Terriers of every type and color. There were always competent men in charge. Mr. Barnard took personal pride in the advancement of his one hobby, the ‘Bullet Headed Dog.’ That these round-headed dogs were the outcome from the original crossing of the Bull on the short-muzzled fighting Terriers, there can be no dispute.’

This statement rather flies in the face of some who claim that the Boston came about through random, haphazard crossings of various breeds. Mr. Boutelle’s account demonstrates, almost from the very beginning, there was a clear purpose by these early dog fanciers to create the perfect, all-around dog breed. They, guided by the talents of Mr. Barnard, were working toward a definite goal and their progress was extraordinarily fast.

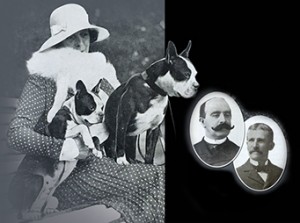

Edward Axtell wrote an illuminating, evocative tribute to Mr. Barnard – the ‘father of the breed’ – and it also tells us about some very important early dogs.

‘I was sitting by the open fire the other evening, and there passed through my mind a review of the breed since I first saw it a great many years ago, when the world, to me, was young. A handsome little lad leading down Beacon Street, Boston, two dogs of a different type than I had ever seen before, that seemed to have stamped upon them an individual personality and style. They were not Bulldogs, neither were they Bull Terriers; breeds with which I had been familiar all my life; but appeared to be a happy combination of both. I need hardly say that one was ‘Barnard’s Tom’ and the other was his litter brother, ‘Atkinson To-by’. Tom was the one destined to make Bos-ton Terrier history, as he was the sire of Bar-nard’s Mike.

Mr. Barnard has rightly been called the ‘Father of the Boston Terrier,’ and he still lives, hale and hearty. May his last days be his best and full of good cheer.

I am now readily approaching the allotted time for man, but I venture the assertion that were I to visit any city or even small town of the United States or Canada, I could see some handsome little lad or lassie leading one of Barnard Mike’s sons or daughters. Small wonder he is called the American dog.

The celebrated Dr. Johnson once remarked that few of our children live to fulfil the promise of their youth. Our little aristocrat of the dog world has more than done so. May his shadow never grow less.’

Enthusiasm for these very attractive, eye-catching dogs quickly gained strength, but the ‘breed’ was still limited primarily to Boston and the surrounding area. With experienced dog breeders taking control, an ideal mental image of what they wanted their breed to look like quickly began to emerge, and the rather miscellaneous assortment of different sizes and shapes began to settle into a definitive Boston type.

However, in these early days not much attention seems to have been paid to color (now such a distinctive part of what makes a Boston a Boston) and a number of the early dogs were indeed mostly white, pied or splashed. More effort was paid to bringing the size down, and as a precaution against the breed becoming too inbred, an occasional dog was imported from England.

In the book, The Boston Terrier and all about it published in 1910, the author comments on these dogs brought from, as he humorously puts it, ‘the other side’ – in other words, Britain!

‘Quite a number of other small dogs were subsequently introduced into the breed, which had become somewhat inbred. These were largely imported from the other side, and were similar in type to Hoopers Judge. One of the most noted was the Jack Reede dog. He was evenly marked, reddish brindle and white, somewhat rough in coat, three-quarter tail, weighing fourteen pounds.

Another very small dog was the Perry dog, imported from Scotland, bluish and white in color, with a three-quarter straight tail and weighing but six pounds.

Another very small dog was the Perry dog, imported from Scotland, bluish and white in color, with a three-quarter straight tail and weighing but six pounds.

It is also interesting to note that a number of early Boston breeders also kept and bred French Bulldogs and these too must have gone into the mix.

Boston breeders were obviously very confident about their distinctive new breed and its future, and felt that this should be confirmed by official recognition from the American Kennel Club. Some forty breeders from all over Boston organized a club and application was made for membership in 1891. The name settled upon for this club was the ‘American Bull Terrier Club.’

This was denied as it was felt that the new breed was not typical of a Bull Terrier and because of vociferous objections raised by Bull Terrier breeders. Round-Headed Terrier (a name by which it had also gone by in its early days) was also turned down. A noted writer and canine authority, James Watson, suggested that as the breed had been bred in Boston, why not name it the ‘Boston Terrier’?

The suggestion obviously went down well.

In 1893 the breed received official recognition as the Boston Terrier and the Boston Terrier Club was admitted to membership in the AKC. Those early Boston lovers quickly set about formulating a standard, and it was one that was written with obvious care. Another famous early Bostonite, Edward Axtell, commented upon this writing:

‘The men composing the Boston Terrier Club, who framed this standard in 1900, were as thoughtful a body as could possibly be gotten together, and they carefully considered and deliberated over every point at issue, and in my estimation this standard is as near perfect as any can be.’

It is quite extraordinary what this small band of Boston breeders achieved in such a short time – taking a hodge-podge of rough ships dogs from England and turning them into a refined, classy, instantly recognized breed, their achievement is truly a lesson to us all. In the early years of the 20th Century, Boston Terrier entries were growing in number at an amazing rate – a popularity that was achieved without the aid of TV/Internet!

Even in the early 1900s it wasn’t unusual for Bostons to already be providing the largest numerical breed entry at dog shows in the Boston and New York areas, and soon this staggering success was duplicated in states all across the USA.

By the 1920s the Boston had come to look very much as he does today. When I compare the photos of my dogs with some of the photos of some of those glorious early champions, I simply have to marvel at what those breeders achieved in such an astonishingly short period of time. One of the kennels that dominated that period was the Haggerty Bostons. A profile of this kennel is featured in Cathy. J Flamholtz’s fabulous book on the breed, Boston Terriers, The Early Years. This book is a MUST for any Boston lover. With its attention to detail and copious photographs, it has to be among one of the finest breed history books written and I have spent many an hour poring over its pages.

In it, a controversy–one that still rumbles in show rings today–is revealed, one pertaining to color.

Under a photograph of Ch. Haggerty’s King, Cathy writes;

‘Born in 1916, Ch. Haggerty’s King was a son of Tiny Ringmaster and is considered a pillar of the breed. He was bred by Mrs. Dan Haggerty and purchased by Mrs. George Dresser for $2,500. He remained her lifelong companion until his death at 10 years of age.

King was a controversial dog. Many felt that he had almost perfect conformation, the ideal blend between the bully and terrier types. He was, in fact, hailed as ‘Faultless King’. The 14 lb. dog finished his championship by quickly taking Winners Dog at Westminster in 1918. He continued to be campaigned but, at a Boston speciality, another exhibitor made a protest on the basis of color and he was disqualified. He was a black and white dog with tan tracings and, under the standard of the time, only brindle dogs were allowed. Many feel that it was due to this incident that the standard was changed to admit black without brindle.

King was a sire of five champions. The number would, undoubtedly, have been higher, but he was never used at public stud.’

Another famous kennel, featured in Cathy’s book, also hails from the Roaring Twenties (one that continued to have spectacular successes into the ‘30s and contributed much to the look of our modern day Bostons) is the ‘Million Dollar Bostons.’

Cathy writes about one of the most illustrious dogs from this famous kennel, ‘Few dogs have garnered as many accolades as Ch. Million Dollar Kid Boots. Dubbed, ‘The miracle dog of all time’ and called ‘incomparable,’ Kid Boots began his career in the late 1920s but really reached his zenith in the early 1930s.

The 12 lb. dog was Best of Breed at Westminster in 1930 and 1932. He was a consistent Group and Best in Show winner, thrilling crowds whenever he appeared. He proved his merit at stud, too, siring eight champions.’

And this kennel would also prove to be important for the breed’s fortunes in Britain. The dog, ‘Million Dollar Boy Blue’, was exported to England to Eveline the Countess of Essex who did a lot to popularize the breed in the UK.

Interest in these dapper little dogs was certainly sufficient for one lady, Mrs. Penn, to make the long journey over to America to study the breed in its homeland. In 1937, Mrs L.E. Salmon’s ‘Massa’s Dollar King’ and Lady Essex’s bitch, ‘Ukansee Disturbers Pride’ each earned two challenge certificates, and the following year they both became champions. The war disrupted the rise of the Boston in England, however, on the resumption of championship shows, Lady Essex was once again a key player and her ‘Ukansee Bobby Socks’ quickly became a champion.

Despite its early promise, the Boston remained something of a minority breed in the UK and Europe. However, quite recently, interest in the ‘American Gentleman’ has exploded. One can only pray that this gorgeous dog, ‘the best breed in the world’ won’t suffer the same widespread exploitation and near ruination suffered by his Gallic cousin, the French Bulldog.

Click here to read the complete article

116 – September 2019

Short URL: https://caninechronicle.com/?p=172377

Comments are closed