The Art of Breeding

Click here to read the complete article

Canyon Crest Kennels

by Amy Fernandez

There are multiple routes to success in this game. Traditionally, star players grew up in the sport. Since World War II that path has been supplanted by the painstaking process of acquiring a pet, falling in love with that breed, learning the basics, and slowly achieving success. Of course, for a few, there has always been that glittery shortcut of buying an invincible contender and launching a career from the top.

There are multiple routes to success in this game. Traditionally, star players grew up in the sport. Since World War II that path has been supplanted by the painstaking process of acquiring a pet, falling in love with that breed, learning the basics, and slowly achieving success. Of course, for a few, there has always been that glittery shortcut of buying an invincible contender and launching a career from the top.

Quite possibly, that was the general consensus in February 1941 when Ch. King Eric v. Konigsbach made history as Westminster’s first Miniature Pinscher group winner. After all, the breed was not a major league competitor back then. Moreover, his owners, Mr. and Mrs. William Bagshaw, had only been in dogs for five years. Better yet, aside from purchasing King a few months earlier, they had zero background in Toys.

However, King was no or-dinary Min Pin as Arthur Fredrick Jones emphasized in his Westminster roundup for the Gazette, “One of the most consistent winners in that final was the excellent Miniature Pinscher that led the Toy Group, Ch. King Eric v. Konigsbach, owned by William O. Bagshaw of Beverly Hills and handled by Russell Zimmerman. This grand specimen is as sound as any dog, large or small, that ever came into the Garden’s final class. He will not be three years old until May but he already has piled up a tremendous record.” (Then 3 BIS and 33 groups of his career total of 10 BIS and 71 groups.) Even so, Jones conceded that his win was a shocker, especially to the rest of that lineup that included Mrs. James Austin’s Catawba Peke, Rosalind Layte’s Burlingame Griff, and Mrs. Vincent Matta’s Moneybox Pom.

Essentially, the Bagshaws bought the best dog in the breed and put him out with a rockstar handler. But anyone inclined to dismiss them as quintessential wealthy dilettantes was in for another shock. Not only were they still dominating the Min Pin scene eight years later, King’s BIS son, Ch. Rajah v. Siegenburg, waltzed in the ring and grabbed the breed’s second Westminster group. Min Pins were only part of a showstring that kept Canyon Crest at the pinnacle of this sport for almost four decades.

Philadelphia-bred Margaret Bagshaw, a self-proclaimed life-long dog lover, met her match in her second husband, Bill. After his real estate development business relocated their family to Southern California in 1929, Margaret decided her three young children needed a watchdog. Danes were popular, and top kennels proliferated in Southern California where the breed’s glamour and visual appeal made it a favorite of Hollywood celebrities.

In 1935 Margaret purchased a two-month-old fawn pup from the famed Planetree Kennel in Encino. As she explained in a 1941 interview for the Gazette, “Achim grew up to fill much more of a spot in the family than we planned, as I feel most Danes do. He enjoyed going hither and yon with me in the car and was very proud when I was in his charge … in less than a year I did not like to go out without this Dane and did not enjoy leaving the children at home without his protection”

Achim’s Freund of Planetree was a pretty nice pet. Within a few months he finished with seven Best of Breed wins and six group placements, becoming one of the breed’s youngest champions. As for Margaret, “the breeding bug had set in my mind with a vengeance”. That led to the purchase of Ch. Heidi of Planetree. Heidi’s first litter by Achim produced their first homebred champion, Andora of Canyon Crest.

The population grew, but the Bagshaw’s Danes remained pets. Their puppies were whelped and raised at home with all the inevitable socialization and habituation of that environment. Although those benefits were just beginning to gain mainstream credence, the resulting temperamental stability provided an obvious edge in the ring.

The show bug had also hit them with a vengeance and they quickly ascended to the stratosphere of West Coast exhibitors. Regardless of money, forging a competitive Dane kennel was no easy feat at that time and place. The Great Dane Club of California was established in 1931. Its roster of founding members was virtually a shortlist of legendary kennels like Estid, Willow Run, and Garricrest. These breeders not only imported German blockbusters, their American-bred Danes had a worldwide impact.

For instance, the club’s first president, Margaret Hostetter, founded Ridgecrest in 1928. She personally handled Ridgecrest’s BIS winning and top producing star, Ger. Am. Ch. Etfa v.d. Saalburg. Her son, Donald Hostetter, became an equally influential breeder/judge. By the 1940s, GDCC supported entries at major shows typically exceeded 100 and the BOB winners frequently topped 600-700 dog groups.

Canyon Crest could have easily cherry-picked show prospects from these sources. However, as Jones explained in his Gazette profile, “The Bagshaws have been interested from the start in breeding as scientifically as possible and have studied hundreds of pedigrees. As a result they have set about collecting worthwhile specimens from as many as possible of the leading strains. They have Hexengold, von Lohenland, von der Saalburg, von Odenwald, von Birkenhof, and von Schloss Stanfeneck,” adding that their kennel wasn’t limited to prospective winners. It included veterans like Ch. Vagabond v. Lindenhof who luckily sired one crucial litter out of Planetree’s Circe before his death, and non-competitive dogs like Ingo of Canyon Crest. Although an injury preempted his show career, Ingo sired numerous influential winners like Ch. Tansy of Canyon Crest CDX, Ch. Ursula of Canyon Crest, Ch. Cliza of Caldane, and Ch. Tonia of Ruhaven.

When Jones visited Canyon Crest, its reigning superstar was Ch. Fabian of Warrendane, who had finished from the Puppy Class and recently sired Heidi’s final litter. His notable wins that year included the GDCC specialty in March and the GDCA specialty at M&E in May. Meanwhile, Andora was bred to another interesting acquisition, Ch. Muldoon. Then three years old, the Bagshaws purchased this big brindle dog from Milwaukee breeder Lee Haggerty in February 1941. Sired by Ch. Randolph Hexengold, Muldoon commenced his show career with a BIS and finished three shows later.

By the end of 1941, the Bagshaws had 20 adult Danes, a score of puppies, and four adult Miniature Pinschers. Jones called it, “one of America’s most notable kennels”. But that wasn’t the reason for his visit. The talk of the dog world was the magnificent Canyon Crest kennel.

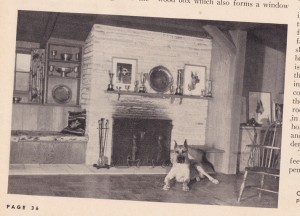

The kennel was definitely nice, but the real story was its spectacular location.

In 1940 the Bagshaws purchased 10.5 acres of undeveloped property in Coldwater Canyon outside Beverly Hills. Constructing this architectural marvel required cutting a ledge into the Coast Range cliffs. “One can stand on the lawn in front of the kennels and see the wide Pacific 11 miles away. In fact, you can see Catalina Island…on the other side the mountains is the San Fernando Valley.” It was situated 1400 feet above sea level and 300 feet above the main highway, which necessitated constructing over a mile of road for access. “But turning off the main highway one must still travel over mile-and-a-quarter to arrive at the kennels,” Jones wrote.

Along with the breathtaking view, the location provided that ideal combination of absolute seclusion and convenience. It was only three miles outside Beverly Hills, seven miles from Hollywood, and 12 miles from L.A. Most importantly, Russell Zimmer-man’s North Hollywood kennel was right down the road. Jones continued, “Although the Canyon Crest Kennel has been active since 1936 it was not until February 1941 that its showing became so extensive that the Bagshaws and the kennel staff could not handle the dogs in the ring as well as care for them at home.” Over the years, Canyon Crest dogs were also presented by Harry Sangster, Percy Roberts, Gus Hill, and Corky Vroom. They had clout. However, nothing ever went out under the Canyon Crest banner until it was fully mature and ready to win.

Zimmerman handled plenty of Canyon Crest superstars but, paradoxically, his headliner wasn’t a Dane. Ch. King Eric v. Konigsback had notched up an impressive record when the Bagshaws acquired him in December 1940. However, he had been out of the ring for awhile, and as Margaret recounted in her 1956 Min Pin Handbook, he was not in good condition. Zimmerman had two months to get him up to speed for the Garden. He shot out of the gate. His Westminster group jumpstarted a year that racked up eight BIS and 56 groups out of 68 BOBs.

Superficially, their jump from Danes to Min Pins seemed incomprehensible. It was undeniably impulsive, but as Margaret explained, “The Miniature Pinscher has well-earned his title as the big little dog. This characteristic first attracted us to the breed.” Although it’s considered a companion dog, it’s descended from classic German working breeds. Tough, fearless, protective, and loyal, Min Pins retain the temperament and working drive of their Pinscher forebears. Admitting that they were “far from Miniature Pinscher-minded” they first encountered King on the San Antonio circuit in November 1939. While waiting to take their Dane back in for BIS he leaped from his handler’s arms to attack the Non-Sporting winner. Mrs. Bagshaw said, “King was most indignant when his handler prevented him from following up his challenge to the Chow, but proudly entered the ring for the final judging. Although he was under a year of age, he won top honors. We were greatly impressed by King’s showmanship, poise, aggressiveness and general appearance, so impressed that at the following show we inquired about the possibility of bringing him home with us. His handler assured us that he was not for sale”. Disappointed but entranced, they followed his career, “then suddenly he seemed to disappear from the show reports. We contacted his handlers and found that he had been sold and his new owner was not showing him. Imme-diately we asked his handler to try to get King for us, as he was just too outstanding a dog, regardless of what breed. On our return to California from Pennsylvania we picked up King in Missouri. He was not in top condition but he was the same fascinating, independent little fellow. He became a great friend of the Dane we were showing at that time. Their birth dates were two days apart but one had grown considerably more than the other during that period,” Mrs. Bagshaw said.

Canyon Crest’s obsession with Danes began with one special dog. That’s exactly how it went down the second time. The Bagshaws loved sharing stories about King’s quirks and charms and clearly adored him. Simultaneously campaigned with Muldoon, this pair of BIS specials inspired plenty of creative advertising. Otherwise, their Min Pin venture was not so much fun. Calling him the “father of the breed in this country”, by the end of 1941 they had acquired and finished three bitches to found their line. Like Canyon Crest Danes, their Min Pin breeding program was defined by top quality. However, from the standpoint of competitive potential, these breeds were worlds apart.

Canyon Crest’s obsession with Danes began with one special dog. That’s exactly how it went down the second time. The Bagshaws loved sharing stories about King’s quirks and charms and clearly adored him. Simultaneously campaigned with Muldoon, this pair of BIS specials inspired plenty of creative advertising. Otherwise, their Min Pin venture was not so much fun. Calling him the “father of the breed in this country”, by the end of 1941 they had acquired and finished three bitches to found their line. Like Canyon Crest Danes, their Min Pin breeding program was defined by top quality. However, from the standpoint of competitive potential, these breeds were worlds apart.

Min Pins were almost unknown outside northern Europe when they arrived here. After 15 years in Miscellaneous limbo they were shuffled into AKC’s newly created Terrier Group with the innocuous title of Pinscher (Miniature). The breed was reassigned to the Toy Group in 1931 but largely remained a non-starter in the ring. As Margaret noted, breeding programs were widely scattered, entries were generally small, and type ranged from “big and clumsy to something more like a Chihuahua…even in 1942-45 our litters did not have the uniformity one expects of an established breed.”

It’s likely that the allure of novelty figured into this Min Pin venture. That’s a perpetually risky temptation in this sport. But that motive couldn’t justify the ensuing effort they devoted to constructing a viable bloodline. Quite possibly, the scope of that task eclipsed the challenges of the daunting transition from Working breeds to Toys. Even so, it was a stroll in the park compared to the hurdle of breaking into the Hound world’s ultimate closed shop, the Greyhound fancy.

Reportedly, the Bagshaws became interested in Greyhounds through their association with prominent players like Percy Roberts who sold them their first one in 1944. Ch. Giralda White Knight, bred by Peter George and imported by Geraldine Dodge in 1938, was sired by Am. Eng. Ch. King of Trevarth out of Parcancady Girlie. Obtaining a dog from Giralda was in itself an accomplishment. As a foundation stud, his impeccable Cornwall bloodlines set the bar high. No problem. The Bagshaws subsequently acquired foundation stock from the DuPont’s Montpelier Kennel, Marjorie Anderson’s Mar-dormere, and Jim and Emilie Farrell’s Foxden.

Although they could have easily stopped there, they weren’t content to stockpile winners, play around, and move on to the next. In short order, Canyon Crest was home to over 25 top-notch Greyhounds like Ch. Foxden Bittern who was bred to Ch. Freelance of Mardormere to produce the renowned Ch. Canyon Crest’s What Of It, Ch. Canyon Crest’s Hourglass, and the top producing BIS Ch. Canyon Crest’s How About It.

Like their drastic leap from Danes to Min Pins, this foray into Greyhounds seemed ostensibly mystifying. From an aesthetic and historical perspective, it made perfect sense considering the shared heritage and structural similarities of Danes and Greyhounds.

In contrast to Min Pin breeding, this didn’t require starting from scratch to instill type and quality. Greyhounds had plenty of that. The problem was getting a hold of it. Like Min Pins, Greyhounds were not numerous. AKC registered about 60 per year and those were distributed among a handful of tightly-controlled breeding programs. There was no free pass into the Greyhound world regardless of money, connections, or credentials in other breeds. The Bagshaws possessed a key advantage which was absolutely essential to gain entry into this exclusive sector of the fancy, aesthetic sensibility. Despite their short tenure in the sport they quickly developed a discerning eye for quality. Their interest was never confined to a single breed or region of the country. They relished seeing and learning everything about purebreds. That, of course, was impossible. It was also impossible to fake that kind of obsessive dedication.

Canyon Crest Greyhounds demonstrated their genuine understanding of type and appreciation for the breed. For decades British imports remained the cornerstone of American Greyhound development and when Canyon Crest brought one over, it was a good one. Their import, Ch. Viverdon Stafarella, was bred to a Bittern son and produced BIS Ch. Canyon Crest’s Splash. His littermate, Fr. Am. Ch. Canyon Crest’s Coronation, became a mainstay of Stanley Petter’s Hewley breeding program.

Like many Greyhound fanciers, they also got into Whippets. Likewise, this was no casual undertaking. Handled by Harry Sangster, the Bagshaws campaigned stars like Canyon Crest Mamie, 1955’s top Hound with eight BIS and 27 groups. The following year they brought out Canyon Crest Teardrop. He was a top ten Hound for 1956-57 accumulating seven Best in Shows and 25 group wins.

This incredibly diverse collection of top winners was sufficient to secure their place in dog show history, which tends to eclipse the broader impact of Canyon Crest. Their dogs seeded countless successful bloodlines. A less direct and arguably more significant legacy was their influence on purebred trends. Interest in Min Pins climbed steadily throughout the ‘40s. Canyon Crest’s headline wins imparted much of the credibility that attracted hardcore fanciers to the breed.

AKC registered 24 Miniature Pinschers in 1941 when King won his Westminster Group. That more than quadrupled by 1950 and continued moving upward. By then, prominent kennels emerged throughout the country and the breed boasted one of the highest percentages of show entries for registered breeds. For example, in 1947 Min Pins racked up 95 group wins. The year’s top Min Pin, Lulabel v. Rochsberg contributed 35 of them. King’s BIS son Ch. Rajah v. Siegenburg also led the charge, including a Group Fourth at Westminster. It wasn’t Canyon Crest’s only Westminster triumph in 1947.

Back then, brace and team classes were tremendously popular, well-supported Westminster events that consistently garnered heavy press coverage. It was a surprise when Gus Hill handled four stunning Standard Manchesters to Best Terrier Team and a bigger bombshell when he returned with Ch. Canyon Crest Firecracker and Ch. Canyon Crest Fire Alarm to win Best Brace in Show. Although this was a non-regular class, the magnitude of the win was colossal considering that Manchesters had competed at Westminster since 1877 without scoring a single group placement.

In a bigger context, Terriers were plunging in popularity across the board, a trend that would continue for decades. Ten years into that post-World War II decline, AKC ranked them as the least popular group of 1956. And Manchesters hovered at the bottom of Terrier registrations. That year’s registration total of 137 reflected a 36 percent drop within two years. Those were precisely the years when Canyon Crest was industriously assembling one of the most dominant bloodlines in the breed’s history. Although this effort was strictly confined to Standards, it ultimately contributed to both Toy and Standard Manchester gene pools. More importantly, Canyon Crest’s aggressive show campaigns revitalized interest in this forgotten breed. Some of the influential lines that emerged in subsequent decades included Salutaire, Pamelot, Fwaggle, Poricia, Golden Scoops, Charmaron, and Renreh.

Reportedly, Canyon Crest’s introduction in Manchesters came via Margaret’s old Philadelphia pal Bill Kendrick. Freeland Kendrick established his Queensbury Terrier kennel around 1900. His nephew continued exhibiting both Bull Terriers and Manchesters under the Queensbury prefix throughout the ‘40s. In a sense; Margaret Bag-shaw’s interests came full circle considering that Wires had been her first breed. However, there was no way to rationalize this endeavor as a potential route to fame and glory, but that was never the point.

Massive kennels like Canyon Crest rapidly became an anachronism in post-WWII America. Various factors sealed their fate, mainly the inarguable fact that overexpansion is a fatal pitfall. With too many dogs or breeds quality is bound to suffer. Usually, it’s true. Few fanciers possess the time, energy, or skillset to effectively manage a large multiple breed operation. However, in this case it worked. Ironically, the primary reason for Canyon Crest’s lasting print on purebred development also seemed increasingly quirky and irrelevant as our sport gradually shifted its emphasis towards those familiar objectives of instant gratification and tangible validation.

None of Canyon Crest’s chosen breeds offered an easy ride to success. That never mattered to the Bagshaws. Obviously, their financial resources imparted the confidence to defy prevailing trends and successfully campaign challenging breeds. Money is certainly a competitive game changer. However, that factor alone never produces a lasting contribution to any breed. The Bagshaws existed at that point where admiration and curiosity intersected to ignite passionate devotion. That esoteric incentive requires a kind of patience, humility and intellectual commitment usually associated with art connoisseurs, not dog breeders. Their real joy came from the process of learning a breed, melding a solid bloodline, and getting it right.

Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=101502

Comments are closed