Olive Cedar: Helping The Brussels Griffon Beat The Odds

Click here to read the complete article

274 – September, 2014

By Amy Fernandez

Brussels Griffon lovers had ample reason to celebrate in 1940 when Rosalind Layte’s owner/handled bitch, Ch. Burlingame Hellzapoppin, triumphed in the Westminster group. A few weeks earlier AKC had awarded her Best American Bred Toy of 1939. After decades of uncertain fortune in America, this double victory confirmed that Griffons had beaten the odds.

The breeder primarily responsible for this miracle is largely forgotten. Olive Cedar’s contribution was profiled by American Brussels Griffon Association VP Iris de la Torre Bueno in the February 1950 AKC Gazette, “Mrs. Cedar was the first to import Griffons to the U.S. at the turn of the century… She was the breed’s pioneer and it is due to her unfailing enthusiasm and continued importations that the breed has gone ahead in this country.”

Her role in Griffon history commenced when transatlantic travel and dog shipping resumed shortly after World War I. Cedar’s initial motivation was purely financial.

Although they were rare in America at that time, Griffons were well-established as a trendy pet of European glitterati. Reviewing the breed’s history two decades later, Hutchinson’s Dog Encyclopedia confirmed, “There was a time when no member of Brussels high society was without his or her Griffons.” Griffons could be a lucrative addition to the inventory of breeds sold at Cedar’s New Rochelle pet shop.

Unlike today, pet shop dogs typically came from quality bloodlines during the early twentieth century. Cedar specialized in the era’s popular breeds such as Bostons, Airedales, Pekes, and Frenchies. Her foundation stock came from respected breeders and many of the dogs she sold were bred at nearby Cedar Kennels, which she owned and managed with her husband, Peter.

Despite their popularity in Europe, American fanciers were decidedly indifferent to Griffons when they arrived in late nineteenth century. AKC admitted them to the studbook in 1899 beginning with Cesar and Flora, a breeding pair imported from Germany by the famed Long Island Dachshund breeder of the era, Rud Schneider. Within a year, regular classes were offered for them at AKC shows, but entries remained sporadic. Cedar took a gamble on its potential popularity as a pet. She began importing from English and Belgian kennels and promoting the breed to her affluent customers. “Very small full-grown, imported specimens coming directly from Brussels always on hand. Reasonable prices.”

From a business standpoint, Cedar’s Griffon venture was successful, as AKC Gazette editor Arthur Fredrick Jones confirmed in his breed profile two decades later, “The breed met with popular favor almost at once and became the fashionable pet of society women and actresses.” The breed’s new niche as fashionable arm candy of East Coast socialites and celebrities was reflected in the changing tone of Cedar’s advertising. “My best recommendations are my numerous customers from all parts of the United States.”

However, she didn’t bargain on one factor. Olive Cedar fell completely in love with the breed. A little later, her adverts featured taglines like, “Once a Griffon fancier, always one.” Her personal enthusiasm was contagious. Her posh clientele may have walked into her shop seeking a stylish pet, but they left as determined novice breeder/exhibitors.

By February 1918, her newly minted Griffon fanciers had joined forces to launch the Brussels Griffon Club of America. Its inaugural specialty at the Park Lane Hotel took place on May 10. This was remarkable progress considering that Griffons had been proceeding at a snails pace. A decade after recognition, the breed’s first champion had finished exactly a decade earlier on February 11, 1908. The impressive turnout of 53 dogs and 30 exhibitors demonstrated the rapid enthusiastic support that Cedar had recruited. Cedar Kennels was represented by 15 entries; half were owner/handled, the balance shown by new exhibitors. The Griffon star burned bright… for awhile. By 1925, 28 of these 30 new fanciers had bailed out on the breed.

Around this time, another of Cedar’s ads confidently stated, “I have owned and bred them for years and have found them to be hardy, easily raised, and exceptionally easy to keep in fine condition.” However, she was an experienced breeder who had been around the block with challenging prospects like Bulldogs, Pekes, and Chihuahuas. Most of her novices had a rather different experience. Moreover, the usual challenges of raising a rare Toy breed were intensified by the Griffon’s notorious genetic instability.

In the April 1934 Gazette, Jones confirmed that Griffons took a dive. “The breed reached its peak around 1920… Indeed, the demand for pets was so widespread that breeders did not concentrate on the showing.” His predictable explanation overlooked the uncomfortable truth about Griffon breeding. It was a work in progress cooked up in the late nineteenth century. Its eclectic heritage was based on Brussels street dogs, known locally as Griffons d’Ecurie. A decade of fast and furious experimental crossbreeding to Affenpinschers, Pugs, Toy Spaniels, French Bulldogs, and Yorkshire Terriers forged an immensely appealing type. Herbert Compton accurately recapped its meteoric rise in The Twentieth Century Dog, “The Griffon made its first bow in public in 1895, and awoke to find itself famous.”

The Griffon was far from ready to meet to the expectations of purebred status when the curtain rose on its main act. That situation became a frequent topic in the English dog press, as shown by this June 1895 account from The Ladies Kennel Journal. “A friend writing from Holland tells me that the pretty Toy Brussels Griffon is not yet an established breed, and breeders find it difficult to breed anything like an even litter of them. Half will be smooth coated, for instance, and of bad color, even when both sire and dam are known to be really good, typical show dogs. Lovers of this variety must not expect to get good specimens at low prices, nor be surprised at queer results when breeding them.” The cream of Cedar’s imports formed the foundation of her breeding program a few years later. They represented the era’s finest bloodlines – but those lines were far from well-established at that time.

The work to stabilize and refine Griffon type was accomplished in subsequent generations by breeders with the grit and determination for that daunting task. The disillusionment of these dilettantes was predictable. Their sudden desertion precipitated the rapid plunge in registrations and entries that Jones described. He confirmed, “the Griffon seemed destined for oblivion in the general dog show scheme of things.” This was an inauspicious juncture for the breed, but Olive Cedar marched on. She continued importing promising stock from her carefully cultivated sources, which made no sense from a business standpoint. Practical considerations had ceased to guide her decisions, but she was ready when opportunity knocked.

A year after AKC instituted group judging, Griffons made history. One of Cedar’s handpicked English imports, a three-year-old red rough-coated dog, Sunnymede Petite Poilu, won the 1925 Westminster Toy Group. He was owned by one of her successful protégés, Mrs. William H. Goff, and traced back to Mrs. Handley Spicer’s legendary Copthorne bloodline. Cedar was laying the groundwork for a solid gene pool, but its potential remained purely theoretical without breeders and exhibitors to maintain the momentum.

The Griffon’s allure as a status symbol had figured into its success from the start. Cedar wasn’t the first or last breeder to leverage that longstanding social cachet to keep the breed afloat. Within a few years, her aggressive advertising made them a magnet for social climbers and wannabes. Although this star-studded roster of celebrities had a negligible impact on Griffon development, they certainly kept the breed in the public eye.

Supporters like this guaranteed ongoing media attention. But a far more influential fancier also emerged during those years. Madeleine Horne Austin, along with her second husband, James Madison Austin, presented some of the era’s most celebrated show dogs. Her association with any breed was guaranteed to get fanciers buzzing, but her interest hinged on the acquisition dogs capable of competing at the highest level of the sport. She dabbled in many breeds, but dropped them quickly if she didn’t get her hands on potential winners. And Olive Cedar’s stock caught her eye.

In October 1932 the breed’s new column in the Gazette announced, “The Brussels Griffon Club of America has just been reelected to AKC membership. One of the oldest member clubs of the AKC, it gradually dwindled and was practically out of existence for many years. For the past two years, members have been working to reinstate the club and they have put on an annual specialty show at the estate of our president, Mrs. J.A. Austin, who has given the club a wonderful helping hand.”

The inaugural 1931 event was won by a Cedar import, Frou Frou du Clos des Orchidees, a red rough-coated dog sold to Austin. A few years later, when Jones remarked that Griffons were “fast marching into the front ranks of dogdom,” he attributed this sea change to another of Cedar’s imports. “It needed a dog of outstanding merit to lead the breed out of this wilderness…Then came Ch. Pi-Et-Ro.” In his typically profuse style, Jones called Petie, “A spectacular Brussels Griffon of such faultless makeup that some of the country’s foremost judges tried in vain to fault him.”

After finishing in four straight shows, Petie was purchased by Austin who won her second Griffon specialty with him in 1932. During 1933, he took Breed and placed in group every time he was shown. More importantly, he lured new fanciers to the breed, a fact confirmed by comparing the 1931 and 1932 specialty entries. Most of the 23 entries in 1931 came from three breeders. The total entry wasn’t much bigger in 1932, but it represented several newcomers.

Austin wasn’t solely responsible for the club’s revival. Another New Rochelle resident and Cedar protégé, Iris de la Torre Bueno, stepped in as secretary/treasurer. Just 20 years old, Iris was born into the dog game. Along with her prodigious work ethic, Iris was also famously strong-willed, opinionated, and outspoken.

An only child, she was raised by her mother and grandmother at their rambling 16-room Victorian home in New Rochelle. Her mother, Celia, was an established Peke and Bulldog breeder before Griffons caught her eye. Considering her devotion to dogs, and Belgian family roots, it’s easy to imagine Celia’s fascination when the first Griffon imports began to arrive at Cedar’s shop.

By the early 1920s Iris regularly accompanied her to Belgium for imports to establish their All Celia Griffon breeding program. It was based on a combination of imports and Cedar’s breeding, which included Iris’s first big winner, All-Celia’s Madamoiselle Griff, and her favorite, Ch. All-Celia’s Antoinette. She described Toinette as, “A living memorial to the devotion that was Mrs. Cedar’s for the Brussels Griffon.” As an impressionable teenager, Iris clearly considered Olive Cedar both a mentor and a role model. She quite possibly inspired the hallmark character traits that set Iris apart as both a breeder and judge.

In her January 1936 Gazette column Iris recounting a watershed incident to illustrate Olive Cedar’s usual approach to Brussels Griffon issues, “Mrs. Cedar dearly loved a good Brabancon and was directly responsible for Smooth classes being accorded to our breed at Westminster. How many remember the year when, in protest at having them judged in classes with roughs, Mrs. Cedar scorned the breed classes at Westminster and entered her Brabancons in Miscellaneous?” She was treading on dangerous ground by instigating mutiny against AKC/Westminster policy. And she won. Decades later, Iris called her, “direct to the point of bluntness and unfailing in her loyalty to the breed.”

Iris was no less domineering and dedicated. However, her attitude towards Smooths was more like a love/hate relationship. A year earlier, the iconic Alva Rosenberg had judged Griffons at Westminster. The reigning Griffon hierarchy was stunned when this universally-regarded authority found a red smooth-coated bitch in the classes and took her all the way to Best of Breed. Iris revealed an undisguised catty streak when recapping the results for her Gazette readers: “Venus made the grade defeating a truly quality lot and was awarded not only BOW but BOB, this will mark the first time in six years that a Brabancon has represented the breed in the Garden group. Elsewhere in this issue you will learn just where Venus placed in the Toy Group.” Needless to say, Venus did not place.

Although the Griffon didn’t place in the group that year, the breed earned its share of Westminster glory. The irrepressible Pi-Et-Ro of Cedar comprised half of the winning brace, shown by another influential newcomer, Mrs. Dan Topping. By 1934, Madeline Austin’s interest was shifting. She backed a series of blockbuster Poms and Toy Poodles that dominated East Coast group competition before settling on Pekes as Catawba’s main breed. She never lost her fondness for Griffons, but several of her important dogs were sold to Mrs. Topping’s Round Hill kennel, including Petie.

In 1934, Jones profiled Round Hill’s sudden, spectacular rise for the Gazette. “It was while an interested spectator at the Griffon ring that Mrs. Topping studied the many splendid specimens shown by Mrs. Olive Cedar.” Topping purchased her first of several Griffons from Olive Cedar in 1929. Ninouche was originally acquired as a pet, but Topping quickly revised her game plan, possibly for the wrong reasons.

While scouting for startup stock, Topping met her future kennel manager. In 1932 she purchased Ch. Rossmoyne Babette from Blanche Robertson, the well-known breeder of Rossmoyne Poms and Griffons. Soon after, Topping pitched her offer. Topping divided her time between Greenwich and New York. Her celebrated kennel was located in Rye. Robertson actually ran it.

Topping concentrated on the shopping end of the business. Within months her buying spree had filled Round Hill with Griffons of every shape, size, color, and variety, including several that were represented to her as pet quality. Like Ninouche, they all ended up in her breeding program. Still, it succeeded for awhile thanks to Cedar’s foundation stock, Robertson’s dog sense, and Topping’s money. When Jones visited for the Gazette, Topping took the opportunity to show off her recent acquisitions – Belgian BIS winner Belzebuth of Round Hill and the Smooth Belgian Ch. Cino, a French BIS winner. Petie’s bracemate, Ch. Doritte of Round Hill, had been shipped over in whelp. Although she lost the puppy, she finished in four shows including Best of Winners at 1933 specialty.

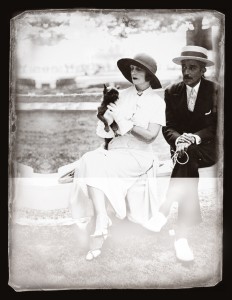

Round Hill’s fleeting fame was soon eclipsed by another rising star and this one was destined to last. In January 1936, the BGCA Gazette column announced, “Mrs. Layte of Burlingame fame, breeder of Russian Wolfhounds and Fox terriers, has gone in for Griffons bringing several females back with her from a recent trip abroad…. we all take sincere pleasure in welcoming her to the ranks of Griffon exhibitors.” Less than a month later, one of these imports, Hitane of Burlingame, took BOB and Group Second at Westminster. A 1920s British film star married to the president of Purolator, Rosalind Layte seemed like another affluent dilettante then pervading the Griffon ranks. In the 1938 AKC Blue Book of Dogs she explained, “One of the darling little monkey faces was sent to me as a wedding gift…I was so excited…really I do not know which got the most attention, the dog or the groom!”

By then, she had just won her third consecutive Westminster Best of Breed with Ch. Burlingame DuBarry and no one doubted her potential. Burlingame was an established name in the dog world before Layte ventured into Griffons. Unlike Topping, she had clear priorities. She kept about 12-15 Griffons, approximately half Belgian and English imports. Within a year the first generation of their progeny confirmed the quality of her bloodline.

The kennel was a main feature of the Layte home. Situated on two acres at the outskirts of affluent Short Hills, the house was described as an authentic English cottage. Both amateur artists, it was decorated with their paintings and rare Oriental porcelain collected during their world travels. The kennel, which occupied the lower level of the main house, was a refitted solarium with wrought iron gates dividing it into pens and runs. It featured a high beamed ceiling, flagstone floor, leaded glass windows, and glass walls etched with canine motifs. Practical, durable, and beautiful, it epitomized her approach to dog breeding.

In her July 1937 column, Iris reported on the record breaking entry of 29 at the recent BGCA specialty held at Morris & Essex. “We take our hats off to Mrs. Layte whose BOB winner, the black Ch. Astral Little Black Sambo, showed like a million!” Continuing her show report, she couldn’t resist some self-promotion noting that Ch. All-Celia’s Magnificent had won the new American Bred class. She also emphasized her disappointment about lack of exhibitor support for this class, which AKC had introduced specifically to encourage and reward American breeders.

Her criticism was prophetic. Two years later, the March 1940 Gazette featured the 1939 winners of AKC’s Best American Bred competition. “The Toy Group laurel was carried off by the Brussels Griffon, Ch. Burlingame Hellzapoppin, bred and owned by Mrs. Rosalind Layte.” By then, Hellzapoppin had also won the group at Westminster. “It was the first Brussels Griffon to appear in the final at Westminster within memory. But then, this is an unusual Griffon. The beautifully put together bitch is bred, owned and handled by Mrs. Rosalind Layte.” It’s unlikely that anyone realized that this double victory represented the crest of the Griffon fortunes. The breed’s success had been built on shaky ground. So far, it had defied the odds but sinkholes began opening up. In retrospect, the factors responsible for the ensuing decline seem clear. But it’s doubtful that anyone grasped the picture at that time.

Many factors had conspired to create that Griffon trainwreck, beginning with Cedar’s publicity blitz over a decade earlier. Her efforts had triggered some activity, which was preferable to stagnation. But Griffons have never been the breed for those seeking a quick payoff of ego gratification. Although well-intentioned, her manipulative intervention had culminated in a spectacular false start and a major setback.

In time, the Griffon might have rebounded, but no one was prepared to wait and see.

Fortunately, the AKC board had not yet implemented its slash-and-burn policy towards failing breeds. Rather than dropping them from the studbook, they generally tried to revive them through heavy promotion and favorable publicity in the Gazette. This time around, the media hype yielded more encouraging results. From a competitive standpoint, the Griffon was small change, but some high profile fanciers like Layte and Austin took the bait. They provided the essential shot of adrenaline that got the breed out of its slump and led to its heyday. Their abundant cash also inundated the gene pool with topnotch dogs.

That combination of quality stock and an active club began luring serious hobby breeders into the ranks. They lacked the means to import dogs of this caliber. But they certainly knew how to utilize them in breeding programs. Their presence explains why the club maintained momentum despite the astronomical turnover rate the breed experienced throughout this era. They were essential to the Griffon’s newfound stability. But their contribution was overshadowed by the stellar achievements of headliners like Catawba, Burlingame, and All-Celia.

The resultant discouraging undercurrent was intensified by the intimidation factor these big names brought to the Griffon ring, which wasn’t completely unintentional. They had been primarily responsible for its revival. Their consequent proprietary attitude was understandable. And by the mid ‘30s, all three had substantially magnified their authority through their role as AKC judges.

The genuine extent of their domination remains speculative, but perceptions about prevailing unfairness demoralized hobby breeders. In one of her last columns as BGCA Secretary Iris addressed this issue. Although it must have been brewing for years, her remarks revealed a stunning lack of insight: “We cannot fail to speculate on why exhibitors turn out en masse at non-local shows with less money offered than at the Long Island and Westchester shows just past, and under a judge who has never had any active connection or experience with the breed. We can recall occasions when some of our most qualified judges have been faced with entries of five or less Griffons.” Needless to say, the names and occasions she mentioned were club specialties judged by members. “Can it be that the opinion of the experts is too conclusive an evaluation; that we seek the hit-and-miss opinions of the uninitiates in preference?”

Burlingame and All-Celia monopolized big wins at major shows throughout the ‘40s. Eventually, this situation led to a major political rift rather than the upturn in Griffon fortunes that Jones had predicted. By then, the breed was stronger, but far from ready to weather that storm. Once again, entries and registrations nosedived. In that respect, it didn’t gain much ground during those 50 tumultuous years.

Olive Cedar’s efforts put Griffons ahead of the game in a much more significant way.

The breed emerged from the wreckage with an incredibly robust, diverse gene pool. The timing was fortuitous. World War II could have easily been the Griffon’s last act. Both Belgium and Britain suffered devastating losses. Most of their Griffon strongholds were obliterated, leaving the breed non-viable in its homeland. Cedar’s relentless promotion and carefully chosen imports ensured that crucial Belgian lines were perpetuated in America. Decades later, descendants of her imports were utilized to revive the Griffon in Belgium.

She died in December 1949 at age 89. Since then, her role in the Griffon’s success has been downplayed. Many aspects of her career violated current ethical precepts. Arguably, a degree of subtlety and sophistication could have offset some of the consequent problems related to her public relations efforts.

Promotion to cultivate interest in a breed has become much more fine-tuned but it remains a tricky job. Because of its potential to fizzle or backfire, many clubs long ago abandoned that conduit to enlist support. Regardless of a breed’s popularity, this has narrowed the field of potential contributions to its future. The Griffon never became a headliner in America, but its genetic integrity has remained solid. In recent decades, its popularity as both a show dog and a pet has slowly and steadily increased.

Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=58596

Comments are closed