Firehouse Dogs of NYC

Click here to read the complete article

By Amy Fernandez

By any definition, America’s fascination with Dalmatians is old news, and generally not the best icebreaker with Dal people. New York’s enduring love affair with the firehouse dog might qualify as a less notorious subplot of this overworked theme. Those spotted dogs have been a hallmark of the NYFD since anyone can remember.

By any definition, America’s fascination with Dalmatians is old news, and generally not the best icebreaker with Dal people. New York’s enduring love affair with the firehouse dog might qualify as a less notorious subplot of this overworked theme. Those spotted dogs have been a hallmark of the NYFD since anyone can remember.

The city’s unshakable devotion to them was confirmed again on January 8 when The Times announced of the death of Twenty, the14-year-old mascot of Ladder Company 20 on Lafayette Street. It became the paper’s most popular story during that news-packed week. Her countless celebrity appearances and familiar presence on the rig made her a longtime community favorite but her fanbase extended far beyond her lower Manhattan neighborhood.

Firehouse mascots like Twenty have captivated New Yorkers for over a century. For instance, way back in September 1910, Jess, mascot of Engine Company 6 on Liberty Street made headlines twice that month. On September 1 The Times first reported her on-the-job injury. “Running in front of the fire chief’s buggy she got too close to the flying hoofs. One of the horses feet struck the dog’s left foreleg breaking it in three places.” Even that sort of emergency didn’t preempt a burning building. “The Chief had to keep galloping to the fire.” Luckily, a neighbor was on the spot. He scooped her up “and carried the injured dog back to the engine house.” Already notified via neighborhood grapevine, the vet was already there waiting for them where he set her leg and ordered her to stay off it. That lasted for ten days. Then the alarm came in from an East River blaze on Pier 5.

“Although her left foreleg was broken and bound in a heavy plaster cast, Jess was so anxious to do her job last Thursday she bolted out of the engine house with the broken, plaster-encased leg held awkwardly in the air and ran on three legs directly in front of the galloping fire horses all the way across town.” She was halfway there when members of Engine Company 6 noticed her running alongside the truck and once again they had no time to stop and take her back to firehouse.” Jess made it safely to Pier 5, watched as her team members did their job, returned to the engine house aboard the truck, and “yesterday seemed none the worse for her feat.” This bizarre episode made more sense in light of her back story. The Times explained that Jess took up residence at Engine Company 6 two-and-a-half years earlier. “She got in the habit of dashing out in a wild state of puppy excitement to every fire that the engine attended. This habit once formed became impossible to break and the company gave her permanent quarters. Whenever the electric bell of the engine house rang an alarm, out the door Jess would dash.”

Although the source of this tradition remains a mystery, by the early 1900s Dalmatians were a standard feature of New York City firehouses. As was the case with Jess, it’s quite possible that it was a unilateral Dalmatian decision to commandeer the job.

Among the breed’s many nicknames, firehouse dog and coach dog seem to have equal sticking power. Actually the Dalmatian’s original purpose remains as controversial as its ancestry. Currently, it is designated as native to Croatia. In reality, its roles have varied as much as its genetic heritage. Thomas Bewick’s History of Quadrupeds is frequently cited as the primary historical source confirming the Dalmatian’s status as a distinct breed. Commenting on it in 1881 for The Illustrated Book of the Dog historian Vero Shaw offered an interesting conjecture about that famous woodblock print.

He wrote, “Of the antecedents of the Dalmatian it is extremely hard to speak with certainty, but it appears that the breed has altered little since it was first illustrated in Bewick’s book on natural history, for in it appears an engraving of a dog who would be able to hold his own in high class competition today with markings that would satisfy the most exacting judges…indeed the almost geometric exactness of the spots represented in Bewick’s engraving impress us with the idea that imagination greatly assisted nature…” Maybe that 1790 illustration owed more to artistic license than reality, but that wasn’t the point.

Shaw continued, “His ideal, however exaggerated, is a standard worth breeding up to in that most important feature of this dog, the brilliancy and regularity of his markings.” That flawlessly spotted image inspired generations of breeders.

Dalmatians made their purebred debut at Birmingham in 1862. However, as Shaw went on to explain, “a great number of these dogs are kept in various parts of the kingdom which are not sent to dog shows and among them we frequently observe specimens of great worth.” Most Dalmatian strains were perpetuated because the breed offered such an awesome combination of visual appeal and functionality. Shaw extolled their versatility as scenthounds packhounds, gun-dogs, and stable dogs, adding “he is capable of showing a very strong attachment to his master and many of them are most excellent guards.”

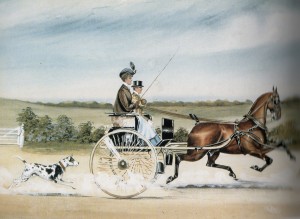

Nothing exceeded the Dalmatian’s popu-larity as coach dog back when a canine advance guard provided a crucial safety measure for horse drawn carriages on cosmopolitan streets. “His love of the stable and the companionship of the horse is his constant ruling passion, and one but rarely developed to the same extent in other breeds.”

True, but they didn’t start out with an exclusive contract as New York City’s firehouse mascot. Virtually any high octane dog with good running gear worked that job. Among others, German Shepherds, Setters, Terriers, and plenty of All-American mixes picked up that paycheck for decades before Dalmatians came on the scene in the 1880s.

Firehouse dogs became standardized along with the department’s uniforms, equipment and procedures and Dals gradually owned the territory. They were the traditional coach dog and no breed could match them for street swag. Still, from a logical standpoint, that job should have gone the way of horse and buggy after 1900 as motorized steam engines replaced horse-drawn fire wagons.

That’s not how it worked. Paradoxically, as the FDNY entered the twentieth century that classic eighteenth century-style icon remained firmly in place as its mascot. Throughout the 1920s and ‘30s as firehouses proliferated throughout the five boroughs so did the celebrity status of firehouse Dalmatians. For example, on April 16, 1934 the harrowing adventure of Jack, mascot of Hook and Ladder Company 105 in Brooklyn, became citywide news. The Times dished it out for maximum shock value:

Dog Hero Escapes Death In Pound

Firemen’s Mascot That Has A Medal For Saving A Life

Nearly Loses Its Own, Picked up Like Any Stray

Adding that the clock was ticking on doggy death row, they reported, “the three-year-old Dalmatian attached to Hook and Ladder Company 105, a dog once feted at the Hotel Astor for one of its brave deeds was saved yesterday. For all its actions of heroism, Jack would have gone straight to oblivion when he was rounded up with strays in Prospect Park last Friday had not an attendant noticed a badge on its collar that bore the letters UFA- Uniformed Firemen’s Association. This prompted a call to the 105th at 648 Pacific Street while several firemen were searching the neighborhood for Jack.” In true Dalmatian fashion, Jack’s varied talent made him an irreplaceable member of the crew.

Adding that the clock was ticking on doggy death row, they reported, “the three-year-old Dalmatian attached to Hook and Ladder Company 105, a dog once feted at the Hotel Astor for one of its brave deeds was saved yesterday. For all its actions of heroism, Jack would have gone straight to oblivion when he was rounded up with strays in Prospect Park last Friday had not an attendant noticed a badge on its collar that bore the letters UFA- Uniformed Firemen’s Association. This prompted a call to the 105th at 648 Pacific Street while several firemen were searching the neighborhood for Jack.” In true Dalmatian fashion, Jack’s varied talent made him an irreplaceable member of the crew.

“Jack’s performance is a matter of pride at the 105th.” Reportedly by listening to a far off engine company’s response to an alarm, Jack knew whether to hop on the truck or run alongside. Of course, his primary function was warning pedestrians and motorists to make way for the speeding fire truck. A couple years earlier he had pushed a child out of its path, which earned him a medal. That was Jack’s crowning glory, but like all firefighters, bravery and dedication was the daily routine. The Times reported, “Jack can climb a ladder, drag a firehose, take a note to the tavern on the corner and bring back lunch for the boys, and sing along with Fireman Joe Denardo’s flute.”

Another of his talents became apparent after Jack’s retirement two years later leaving the 105th without a mascot or any security. According to this August 12, 1936 follow-up story, “Although housed only two blocks from Brooklyn police headquarters, members of Hook and Ladder Company 105 yesterday appealed to fellow firemen for a Dalmatian pup to safeguard their valuables while they are answering alarms. The request followed a series of robberies at the firehouse which began after Jack retired.” Reporting on the latest incident, it reported, “Shortly after 5:00 last Friday morning the firemen returned from a false alarm after eight minutes to find their radio, coffeemaker and coffee mugs stolen.” As their job description expanded and they became an inseparable aspect of FDNY culture, it’s not surprising that breeding firehouse dogs became part of the tradition. On November 20, 1936 The Times announced the death of Rex. He had served as mascot of Engine Company 9 since 1927, and during those years his job also included siring 75 percent of the NYFD’s mascots.

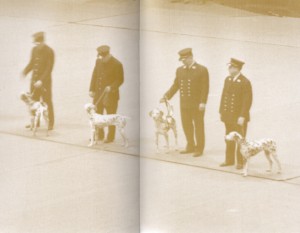

Fire companies were justly proud of their mascots. Until AKC revised the rules in 1924, Westminster frequently offered special classes for working firehouse Dalmatians, which were usually shown by firefighter breeder/owners. During World War II, Dogs for Defense refocused national attention on canine heroes, which prompted a revival of this special event at Westminster 1941. It was reported, “Dalmatians should ex-perience a surge of popularity after that splendid display made by 25 uniformed New York City firemen with the firehouse dogs. These were the finalists of some 80 that had competed, and judging was by Fire Commissioner John McElligott, Col. John Reed Fitzpatrick, President of MSG, and Gerald Livingston, president of Westminster. King, handled by Joseph Donnelley of Engine Company 311, was the winner; Bonnie, handled by Richard Garrett of Hook and Ladder Company 158 was second, and Patches, handled by Joseph Melcher of Engine Company 142 was third.” To top off this Dalmatian Celebration, Ch. Tally Ho Sirius, bred and owned by that matriarch of DCA, Mrs. Leonard. W. Bonney, was Group Third.

This ceremonial salute highlighted the ongoing public adoration for New York’s firedogs. However, by the end of the decade the tradition was on the wane. The Brooklyn Kennel Club learned that the hard way. The November 24 Times announcement of their upcoming December 3 show highlighted its major attraction, “Firehouse Dogs Will Vie in Show…Firemen are stealing a little time from polishing brass these days to groom their Dalmatians for a special competition for New York fire dogs.” Despite the sterling silver trophy on offer this event drew only seven entries, three from Brooklyn, three from Manhattan, and one from the Bronx. By then, only 100 of the city’s 250 firehouses had mascots. The veteran among them was thirteen-year-old Cappy, retired but still holding down the fort at Engine Company 65 in Times Square, one of the city’s oldest and busiest. The Times reported, “to look at his rheumy eyes and gray whiskers, you would not think that Cappy was formerly the glamour dog of the advertising business.” Over the years his image had promoted everything from soap to whiskey and air travel, and raised donations for the March of Dimes. Cappy undeniably earned his keep as a mascot, but he made it to that ripe old age simply because he never served as a working firedog.

Despite the glamour, tradition, and public adoration, firefighting remains a perpetually dangerous profession. All of those of heroic and heartwarming firedog stories were balanced by an equal number of tragic accounts of firehouse mascots losing their lives performing their job alongside their human partners. Budget cuts, lifestyle changes, and all those other dreary realities of life certainly contributed to their fate, but that was the primary reason why fire dogs faded off the cultural map during the ‘50s. America’s wartime appreciation of hero dogs was part of an overall social trend that heralded a new sense of responsibility toward our canine workforce.

Twenty was the exception to that rule. She arrived at Ladder Company 20 at a crucial moment and she was old school. Squad 18 and Ladder Company 20 shared space on Lafayette Street a mile from the World Trade Center. The 343 firefighters who died in Lower Manhattan on 9/11 included seven members from each company. Firehouses throughout the city were inundated with appreciative gestures over the next few weeks. Along with cards, donations, and gifts, a spot-on token of thanks arrived from the upstate New York Monroe County sheriff’s department… a liver-and-white Dalmatian pup. True to her heritage, Twenty needed no introduction to the life. It was love at first sight the moment she saw that fire truck. She was a classic fire dog. She slept and ate with her firefighters, and five alarm or false alarm, for a decade she was onboard the rig for every run.

Throughout those years she also performed another essential service. Although not unique to firehouse dogs, it goes with the tradition. The comfort and moral support she provided meant more than anything in that particular time and place. She retired five years ago, but true to form she remained at her post until January 8, 2016.

Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=97602

Comments are closed