The Boerboel – The South African Mastiff

Click here to read the complete article

114 – September 2019

Text and illustrations by Ria Hurter

Most dog writers start the history of the Boerboel at around 1000 BC. They refer to Assurbanipal, King of the Iron Age Neo-Assyrian Empire from 668 BC to ca. 627 BC. One of the few kings in antiquity who could read and write, he became known for the Library of Assurbanipal, a collection of thousands of clay tablets dating from 7th century BC, that is now in the British Museum in London.

These tablets include depictions of a lion hunt with dogs. These strong-headed, strongly muscled, hunting mas-tiffs are often incorrectly ident-ified as the forefathers of dogs that instead descended from the Molossian Dog – the Tibetan Mastiff, Great Dane, and Spanish Mastiff, for example. The Assyrian hunting mastiffs were bred to grip and hold. The Molossian dogs were flock guardians and hounds of the chase (The Mastiffs. The Big Game Hunters. Col. David Hancock, Charwynne Dog Features, 2005).

The ancient Roman poet Grattius (or Gratius Faliscus, 63 BC to AD 14) wrote of British mastiffs, describing them as superior to the ancient Greek Molossus. “What if you choose to penetrate even among the Britons? How great your reward, how great your gain beyond any outlays! If you are not bent on looks and deceptive graces (this is the one defect of the British whelps), at any rate when serious work has come, when bravery must be shown, and the impetuous War-god calls in the utmost hazard, then you could not admire the renowned Molos-sians so much.”

What about the word “molosser”? In dog literature, the terms “molosser” and “mastiff” are often used interchangeably. Sometimes, “molosser” is simply translated as “mastiff.” Dog writers from the past wrongly linked any large, heavy dogs to the Molossian dogs and labeled them molossers. Breeds such as the Dogue de Bordeaux, Mastiff, Bullmastiff, Fila, Brasileiro, Broholmer, etc., that are currently listed by the FCI under Molossoid Breeds, are not descendants of the Molossian dogs of antiquity. They were only labeled as such.

The word “molosser” is derived from Molossia (Epirus), a region in ancient Greece.

During the 17th century, the Netherlands distinguished it-self in seafaring and coloni-alism. It was the golden age of arts, sciences, and the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Com-pagnie, VOC). The Company founded a staging post at the Cape of Good Hope – the Cape Colony – in 1652.

When colonial administrator Jan van Riebeeck (1619-77) arrived in South Africa and disembarked at Table Bay in 1652 , he was accompanied by a Bullenbeisser – “bull-baiting dog” – not for hunting, or fighting bulls, but for the protection of his family. His dog was described as “a bull-baiting dog of the mastiff type.”

Double Dentition

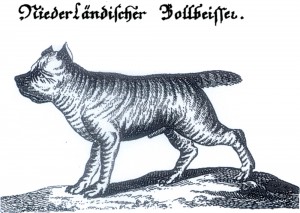

In the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, in the Netherlands, as well as in Germany, were various types of mastiffs; such as the so-called bull-baiting and bear-baiting dogs (Bullenbeissers and Bärenbeissers), and Molossian dogs.

In his Der vollkommene Teutsche Jäger (The Complete German Huntsmen; 1719), German dog writer Hans Friedrich von Flemming gave a detailed description of these dogs: “…medium dogs, but heavily built. They have a broad chest, a short, thick head, and a short, sloping nose. Pricked, pointed, and cropped ears and a double dentition. It’s thus that they hold the prey. Their movement is ponderous, but they are strong, heavy, and well-fleshed. Apart from the large Danziger Bullenbeisser [Dan-zig is a city in eastern Germany], another variety lives in Brabant [part of the historic Low Countries]. They are medium-sized and mostly smaller than the Danziger, but as far as limbs and construc-tion, they are the same. Their name is Brabanter Bullen-beisser. In case there are not enough bears, they are trained to pursue bulls or oxen, although, this is a sport more suited to a butcher than to a hunter.”

Jan van Riebeeck became the first governor of South Africa. His ship, the Dromedaris (Dromedary), was loaded with sheep, but also carried materials and tools to build a fort. He lived in the area of the Khoikhoi tribe, whose dogs resembled sighthounds and contributed to the development of the Rhodesian Ridgeback. Apart from the Dutch, settlers from Germany, England, and France brought their dogs as well–to protect their families and belongings.

English Bullmastiffs and Bulldogs were imported during the second Boer War in 1902. These dogs were crossed with the local dogs and the result was the so-called Boel, a forerunner of today’s Boerboel. Many South African farmers used the Bullmastiffs from England on their Boels, an important step in the Boerboel’s history.

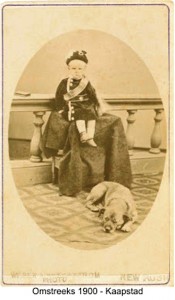

The first part of the breed’s name is the Dutch word for farmer – Boer. The second part came from “Boel,” an old Dutch-Afrikaans slang word for “dog,” as the type was called around 1900.

Notwithstanding a ban on colonization, the Cape was colonized on a broad scale. In 1795, the British effortlessly took control from the Dutch and kept the Boer people under their thumb. It was the beginning of De Grote Trek (The Great Trek) inland that started about 1840 when the Boers founded large and small independent republics – for example, the Transvaal and Oranje Vrijstaat (Orange Free State). They had had enough of the wars with the Xhosa tribe, the immigration of the English, the meddlesomeness of the British missionaries, and the threat to the Dutch language by the English language.

Farmers in the remote interior of South Africa had urgent need of an impressive and versatile dog. The families wanted an imposing, multi-functional, strong, tough, self-confident, and loyal dog with a stable temperament. This was no place for an aggressive or disloyal Boerboel. Because families in the various Boer republics led isolated lives, they had to be able to count on their protectors.

In the beginning, there was quite a lot of inbreeding, which established characteristics within a short period of time. However, at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, these characteristics slowly disappeared. The result of foolish crossings, and breeding with anything “that had four legs” was that the Jan van Riebeeck dog, or the typical Boel, became nearly extinct. Urbanization increased the process.

It took some time to find original Boels in the 1980s, when serious attempts were made to restore the breed. In August, 1980, Jannie Brouwer, from Bedfort (Eastern Cape), and Lucas and Anneke van de Merwe, from Kroonstad (Orange Free State), traveled over 3,000 miles to assess 250 dogs, of which 72 were selected for registration and a breed program. The 72 are now considered to be the first official Boerboels in South Africa.

In 1983, Johan de Jager from the Natal province, a Boerboel breeder since 1960, took the initiative to found the South African Boerboel Breeders Association (SABBA).

The association was eventually dissolved and merged with the South African Boerboel Breeders’ Society (SABBS; sabbs.org) in 2014. The SABBS is responsible for the breed standard, identification, evaluation, and improvement.

The South African kennel club – the Kennel Union of South Africa (KUSA), 1891 – has two national breeds, the Boerboel and the Rhodesian Ridgeback. They have some forefathers in common.

The AKC describes the Boerboel as “a dominant and intelligent dog with strong protective instincts and a willingness to please. When approached is calm, stable and confident, at times displaying a self-assured aloofness. He should recog-nize a threat or lack thereof. He is loving with children and family. An aggressive or belligerent attitude towards other dogs should not be faulted. Boerboels that are shown in competition should be trained to allow examination.”

A Boerboel loves the whole family and enjoys their company. Boerboels living in solitude become frustrated and develop destructive behavior. During training, the breed needs a strong but loving hand; training has to start as early as possible.

Care must be taken with puppies and young dogs, whose legs can be easily overstrained. High quality food will keep the dog in shape. Its short, dense coat needs minimal care, but the area around its mouth must be cleaned, as some dogs may dribble.

For coat color, all shades of brown, red, or fawn, with limited, clear white patches on the legs and the forechest are permissible. Brindle in any color is acceptable (AKC standard).

The Kennel Union of South Africa does not accept a black coat but the SABT (South African Boerboel Dog Breeding Association) does approve of that color.

Height at the withers for dogs is 24 to 27 inches (61 to 69 centimeters); for bitches it’s 22 to 25 inches (56 to 64 centimeters). (AKC standard). The Boerboel’s lifespan is about 12 years.

In November, 1994, 12 Boerboels arrived to the Netherlands by plane from South Africa: one adult and 11 puppies from four different litters. Before leaving South Africa, the adult bitch had been mated by one of the top dogs in the country. Shortly after her arrival, a litter of five was born.

It is not generally known, but a Boerboel is a versatile breed. There are Boerboels with AKC titles in herding, obedience, rally, agility, therapy dog, and coursing. Some are really good tracking dogs. Nowadays, in South Africa, Boerboels are still used as working dogs and guard dogs. However, the Boerboel is absolutely not a dog for everybody. Socialization and training must start at an early age.

Sometimes the inheritance of characterisics from the breed’s forefathers can be seen. In my family are two Boerboels, an adult bitch and a male puppy. The bitch has a lovely, typically molossian head. The puppy’s head resembles that of an old bull-and-terrier cross.

Hip dysplasia, entropion, ectropion, tumors, cleft palates, epilepsy and, now and then, skin and ear problems occur in the breed.

Something About the Boerboel in America

Something About the Boerboel in America

The Boerboel was introduced to purebred enthusiasts worldwide by the American anthropologist Dr. Carl Semencic in his book Gladiator Dogs, published by T.F.H. Publications in 1998. Dr. Semencic’s information came from his correspondence with the head of the first South African Boerboel club, Kobus Rust.

In 2006, the Boerboel was accepted for recording in the AKC Foundation Stock Service (FSS). In 2015, the breed became a member of the AKC Working Group. The American breed standard can be found at akc.org/dog-breeds/boerboel.

Aside from the breed clubs in South Africa and America, there are numerous Boerboel clubs, Facebook groups, etc., in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, England, Czech Republic, and more. At this time, European Boerboel breeders and owners seem not to be interested in recognition by the FCI.

Banned and Restricted

For various reasons, the Boerboel has been banned in some countries. In 2010, Denmark banned the Boerboel for being a fighting dog (Currently existing dogs must be muzzled and leashed at all times in public). In 2011, Russia designated the Boerboel an “especially dangerous breed,” as did the Ukraine. In 2002, Romania prohibited the import of the Boerboel, and France banned the breed. In Denmark and Romania, owners must be at least 18 years old and certified psychologically fit to own a Boerboel. In Malaysia, Tunisia, Qatar, Singapore, and some other countries and cities, the Boerboel is banned, illegal, or prohibited. In Singapore, currently existing dogs must be covered by insurance in an amount no less than $100,000, be sterilized, microchipped, and muzzled.

Owners must recognize that owning a Boerboel requires a significant commit-ment of time and energy. Nevertheless, thousands of Boerboel lovers worldwide enjoy the breed. Properly raised and trained, the Boerboel can be a protector and friend for life.

We have tried to find the names of all photographers. Unfortunately, we do not always succeed. Please send a message to the author if you think you are the owner of a copyright.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A retired bookseller and publisher, Ria Hörter is a dog writer from The Netherlands. She is the contributing editor of the leading Dutch national dog magazine Onze Hond (Our Dogs) and works for the Welsh Springer Spaniel Club of the Netherlands of which she was one of the founders. She served the club for 44 years, as secretary and chairman and is a Honorary Life Member of this breed club. She was nominated twice, and a finalist in the 2009 Annual Writing Competition of the Dog Writers Association of America, for her articles in Dogs in Canada.

On April 12, 2014, she was awarded the Dutch Cynology Gold Emblem of Honour. The award was presented by the Dutch Kennel Club.

For more information visit: riahorter.com

Click here to read the complete article

114 – September 2019

Short URL: http://caninechronicle.com/?p=170030

Comments are closed