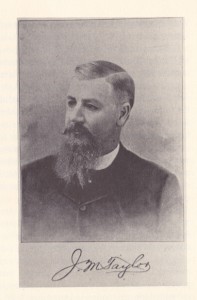

AKC’s First President – James M. Taylor

Click here to read the complete article

By Amy Fernandez

AKC is generally considered one of those impenetrable bluechip organizations. It probably seems that way now, but it didn’t simply arise in full corporate splendor on Madison Avenue. That daunting image was a century in the making. Along the way most of the good stuff was consigned to history’s dustbin, such as the interesting tenure of its first president, Civil War veteran Major James M. Taylor.

AKC is generally considered one of those impenetrable bluechip organizations. It probably seems that way now, but it didn’t simply arise in full corporate splendor on Madison Avenue. That daunting image was a century in the making. Along the way most of the good stuff was consigned to history’s dustbin, such as the interesting tenure of its first president, Civil War veteran Major James M. Taylor.

Taylor initially emerged in purebred history as an organizer of America’s first field trial sponsored by the Tennessee State Sportsmen’s Association and held on October 7-8, 1874. That’s the official version. Actually, it was a combined bench show/field trial – and definitely not the country’s first field trial. That impressive but technically inaccurate desig-nation resulted from two key details, its focus on Gundogs and adherence to Kennel Club rules introduced a few months earlier. Like most of Taylor’s long, influential contributions to America’s fledging dog scene, the gray areas far overshadow black and white facts.

Kentucky born and bred, Taylor came straight out of the cultural traditions that forged renowned Foxhound strains like Trigg and Goodman. In 1904, Joseph Graham documented this uniquely American conduit of purebred development in The Sporting Dog writing, “there was a great deal of good breeding before the days of public competition….in America the foxhound was largely developed by a survival of the fittest in private contests”. While noting their value as a selective breeding tool he added, “A record of superiority is not standard until it becomes public”.

By the 1860s those contests were on the record. Kentucky’s first widely publicized field trial took place in Madison County on April 25, 1866. Official rules and extensive coverage by publications like Turf, Field, and Farm reflected growing mainstream interest in this evolving sport. That momentous 1874 event didn’t suddenly materialize out of nowhere. Likewise, American Gundog breeding dated from colonial times. America had plenty of Pointers and Setters, but they were strictly hunting dogs. That fancy new field trial type coming out of Britain was fast, sleek, and built to win. This canine Ferrari was poised to become national obsession.

It was taking root when Graham first encountered it as a boy on “a Virginia day in the winter of 1863 peeping through a fence of chestnut rails to see a redhot Confederate landowner, a Federal officer, an old white Setter and a bevy of quail”. This shared appreciation transcended social and political boundaries then tearing this country apart. It underlies every aspect of purebred dogs, but it wasn’t the only influence shaping American field trial culture. Fierce undercurrents of possessiveness and oppor-tunism were also firmly embedded in the sport by 1874. The Civil War wasn’t neatly confined within those historical bookends of 1861-1865. It was preceded by years of sporadic conflict, economic volatility, and political insecurity. A decade later, those polarizing forces still reverberated through every strata of life south of the Mason Dixon line.

When it came to surviving and thriving in this challenging era, Major James Taylor wrote the book. Ambitious and attuned, he recognized that his legacy of dog know-ledge was suddenly a bankable commodity. He was a progressive thinker but far from the only entrepreneur deter-mined to capitalize on this budding oppor-tunity. Leading the pack was his contemporary, Arnold Burges, another dog crazy Kentucky boy. Thanks to his family wealth, by age 30 his Setter obsession defined his life. After establishing his Rob Roy kennel in 1868, he focused on documenting the scene, most notably through his 1876 work The American Kennel and Sporting Field. Considered the first American studbook, it was actually a more personal endeavor, chronicling and validating his role in this pivotal era.

That proprietary focus wasn’t an aberration. Dr. Nicholas Rowe was living proof. After a brief medical career, an advantageous marriage became his gateway to a full-time dog business. Rowe’s remarkable stockpile of Gundog imports qualified him as the biggest fish in this little pond. And that led to his dream job editing a minor league Chicago sports weekly. Within five years he turned it into America’s supreme dog publication. Blatantly self-serving and ethically adaptable, Rowe used American Field to promote, manipulate, and dominate an increasingly lucrative niche of purebred sports.

Breeding, brokering, and journalism became the standard career formula for most of the pioneering spirits of America’s dog game. In contrast to those financially reliable pursuits, formal Gundog trials were a dicey proposition. The concept had some traction in Britain – but that assessment was based on a dozen events staged over eight years. In reality, little evidence suggested big potential for it in America. Inveterate gamblers, Taylor and Rowe couldn’t resist. The first trials in summer of 1874 drew two and three entries respectively. That apathetic response seemed to confirm its fate as another quirky English pastime. At that point Rowe switched to the less risky venture of bench shows. Taylor prepared for relaunch. Rowe’s October 7 event on Long Island was successful enough to qualify as America’s first bench show. Meanwhile, down in Memphis, Taylor’s group cast a wider net presenting a combined bench show and field trial the same weekend. Both drew double digit entries, which signaled a comparatively encouraging upsurge. However, a local Pointer breeder contributed most of Rowe’s entry, and members of the Tennessee Sportsman’s Association provided a major portion for their show, including Maud, the grand prize winning English Setter pup, imported by one show sponsor, Ontario breeder/broker L.H. Smith and owned by another, P.H. Bryson. Based in Memphis, Bryson and his brother, David, also emerged front and center of this scene.

Breeding, brokering, and journalism became the standard career formula for most of the pioneering spirits of America’s dog game. In contrast to those financially reliable pursuits, formal Gundog trials were a dicey proposition. The concept had some traction in Britain – but that assessment was based on a dozen events staged over eight years. In reality, little evidence suggested big potential for it in America. Inveterate gamblers, Taylor and Rowe couldn’t resist. The first trials in summer of 1874 drew two and three entries respectively. That apathetic response seemed to confirm its fate as another quirky English pastime. At that point Rowe switched to the less risky venture of bench shows. Taylor prepared for relaunch. Rowe’s October 7 event on Long Island was successful enough to qualify as America’s first bench show. Meanwhile, down in Memphis, Taylor’s group cast a wider net presenting a combined bench show and field trial the same weekend. Both drew double digit entries, which signaled a comparatively encouraging upsurge. However, a local Pointer breeder contributed most of Rowe’s entry, and members of the Tennessee Sportsman’s Association provided a major portion for their show, including Maud, the grand prize winning English Setter pup, imported by one show sponsor, Ontario breeder/broker L.H. Smith and owned by another, P.H. Bryson. Based in Memphis, Bryson and his brother, David, also emerged front and center of this scene.

A handful of similar trials took place over the next year but none rivaled the Tennessee Sportsman’s Association’s follow-up extravaganza on October 27, 1875. Its awesome enticements included a newly invented title, Championship of America, and an unprecedented number of classes offering hefty cash awards topped by a $250 grand prize (about $5000 today). That somewhat offset the steep $25 entry fee. Somehow, most of the cash was recycled right back to the promoters. The show’s other notable feature was the inescapable conflict of interest pervading the whole thing. Along with organizing the show, Taylor also judged, as did his friends/business associates Smith and Rowe. Rowe’s Pointer and Taylor’s English Setter Maud (purchased from Bryson after her win the previous year) were the big winners.

From a contemporary perspective, this appears unbelievable. Not so much when it’s considered within historical context. Conventional standards and practices of American business were flying off the rails as banking, politics, industrialization, and commerce melted into exploitative monopolies and trusts. The Tennessee Sportsman’s Association wasn’t Standard Oil but it utilized the same revised ground rules that heralded the rise of the corporate economy.

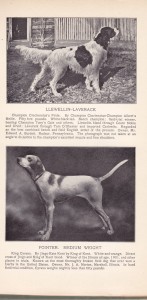

Nothing exemplified this business model better than the rise of the Llewellin Setter. Variously considered a type, strain, or bloodline, the exact nature of a Llewellin broadened along with its popularity. For several years prior to this Taylor and his peers had industriously constructed foundation breeding programs from Llewellin stock. All of their subsequent ventures neatly interlocked to foster a consumer base for their product.

Llewellin’s dogs did okay in British trials. Like any large kennel, some were good, a few great, and others best forgotten, a fact ironically noted by numerous journalists at the time. Incredibly, every Llewellin that stepped off the boat was a rock star. It was no wonder, considering who controlled every phase of the process was also responsible for their stellar reputations. Taylor made the rules, oversaw judging of the events, recording of the results, bestowing the awards, and producing the subsequent show reports. Among the first Llewellin superstars was Gladstone, imported by Smith and owned by Bryson. According to Graham, “Gladstone won on the bench as well as in the field, but it was probably the prestige of the dog as well as the somewhat irregular character of bench show entries in those days rather than his strict show qualities which gained him the ribbons.”

They were thinking big, but not quite big enough. NAKC’s lopsided focus on field trials may have simply reflected their personal comfort zone. Equally possible was the fact that Llewellins fared markedly better in that realm. The interesting thing about Taylor was his conspicuous absence from this audacious power play. Like the rest of them, he was up to his eyeballs in Setter field trial business, but it wasn’t the only game in town.

Bench shows were proliferating and raking in profits from an untapped segment of dog lovers. That fact became abundantly clear a few months later when Westminster’s inaugural 1877 show vastly exceeded all expectations for consumer appeal and financial success. Moreover, NAKC’s tacit policy essentially relinquished involvement in that entire sector of the sport, leaving clubs to devise and enforce their own rules with varying success. Westminster’s version appeared in the The New York Times prior to its next show. This weird, fragmented arrangement was the deal for several years as every facet of the sport grew.

As the stakes got higher, all of these brewing issues coalesced into a game changing incident at Westminster 1884. As Watson noted, Westminster “was essentially a Pointer club”. It was also a bench show club because that became the route to success for most Westminster Pointers. The club’s success grew right along with their preferred niche, which by then rivaled the financial and political clout of NAKC.

At that point Taylor had creatively positioned himself with a foot in each camp. Perhaps he was more visionary or merely more opportunistic than his NAKC cohorts. As Watson explained, “Setters were the popular shooting dog of that period, but quite a number of good Pointers were being imported”. Taylor facilitated a good portion of those transactions and was justifiably considered among the country’s premier Pointer authorities. Whatever his motives, it certainly suggested that he had a better grasp of the big picture. And that took on a whole new meaning after May 6, 1884.

That was the day E.C. Sterling, a prominent St. Louis pointer breeder, stepped in the ring to judge the breed at Westminster 1884. It’s hard to fathom why the club invited him considering his extensive personal and political relationships within the breed. They were courting trouble and it commenced the moment the slate was published and Sterling’s St. Louis co-breeder, John Munson, announced his intention to exhibit. Although Westminster rules prohibited entering dogs co-owned with judges, Munson showed up with two technically ineligible entries.

That was the day E.C. Sterling, a prominent St. Louis pointer breeder, stepped in the ring to judge the breed at Westminster 1884. It’s hard to fathom why the club invited him considering his extensive personal and political relationships within the breed. They were courting trouble and it commenced the moment the slate was published and Sterling’s St. Louis co-breeder, John Munson, announced his intention to exhibit. Although Westminster rules prohibited entering dogs co-owned with judges, Munson showed up with two technically ineligible entries.

As The Times reported, things were tense at the Pointer ring and rapidly worsened as Munson won multiple classes with both dogs. That was only a warm-up. “The great contest lay between Meteor and Beaufort.” Meteor, an eight-year-old liver-and-white dog imported in 1881 was reportedly valued at $10,000. The Times omitted the more pertinent detail of his joint ownership by Sterling and Munson. It reported, “Beaufort is owned by C.H. Mason….liver and white four years old…equally well-bred and competitively successful…the owners of these two dogs were full of rivalry.” Adding a little more fun to this powder keg, The Times reported, “the owners of the two dogs backed their opinions in a substantial manner and $5000 changed hands on the decision of the judge, and he devoted a great deal of time and care to his work. Every point was carefully considered.” Sterling deliberated for 30 minutes. Rather than deescalating the tension, his dithering display incited raucous ringside support from both factions. “The big crowd gathered around the judging enclosure was intensely interested in the contest. Finally the prize was awarded to Meteor,” said the report. The Times downplayed that nasty scene, but the media wildfire was already out of control.

Beaufort’s owner, Charles Mason, a notoriously contentious character under the best circumstances, arrived at the show packing trouble and got down to it immediately. Complaints to Westminster officials and a barrage of slanderous remarks to the press were followed by a stream of venomous editorials accusing Sterling and Munson of fraud, bribery, dog switching, incompetence, and worse. Mason packaged all of it into a petition demanding justice, the infamous Pointer Protest. Within days, it went global. Watson (a Beaufort fan) gleefully watched the drama unfold. “The result was the most aggressive correspondence ever published on dog matters in any country.” Most of the dog press treated it like front page news, and it dragged on for months, and that was back when every contribution required writing and posting a letter.

However, very little media response qualified as objective journalism, simply because all the major players had skin in the game, including Mason. Like the rest them, his activities as a breeder, judge, importer, broker and journalist overlapped in questionable ways. American Field tried to hedge its bets with a neutral stance, its only realistic recourse by then. They wrote, “The very large number of communications on the pointer protest which we have received forces us to either cease publishing them or give the whole paper up and continue an almost endless publication of them.”

Yes, Munson shouldn’t have entered, Sterling should have excused his dogs for multiple reasons, and Westminster should have cancelled the awards and disciplined Mason for his antics. It’s hard to understand how anyone expected to get away with it, but they did. Westminster wasn’t keen to jump in and acknowledge complicity or negligence OR jeopardize crucial personal loyalties representing their cornerstone of the sport. By then, America’s presumptive authority in this situation, NAKC, had the legislative credibility of the wizard of oz.

The Pointer Protest was a juicy scandal but the true source of its unending controversy was much more profound. The subjective nature of judging inevitably invites criticism. But the real issue at stake was territorial control of the sport. It triggered the collective realization that, ten years into the deal, America’s flourishing dog game had no legislative recourse beyond the court of public opinion. Eventually, the mêlée ended in a stalemate with a single point of agreement, as American Field noted August 23, 1884.

“Many breeders are being driven out of the bench shows by these problems. At present no subject is of such interest to breeders and exhibitors as the organization for the purpose of making and enforcing laws”. Without effective leadership to restore confidence, this ship was going down.

Short URL: https://caninechronicle.com/?p=98657

Comments are closed